![]()

Allyl Isothiocyanate

The key ingredient of mustard

![]()

Simon Cotton

University of Birmingham

![]()

Molecule of the Month January 2024

Also available: JSMol version.

![]()

|

Allyl IsothiocyanateThe key ingredient of mustard

Simon Cotton

Molecule of the Month January 2024

|

|

Allyl isothiocyanate ... that's a bit of a mouthful!

Allyl isothiocyanate ... that's a bit of a mouthful!Indeed, and in more ways than one!

Not as such; you get it from sinigrin.

Sinigrin is a glucosinolate. Its proper chemical name is 2-propenyl glucosinolate.

|

| Sinigrin |

They are plant secondary metabolites; these are compounds made by plants which are not vital to the life and growth of the plant, but serve some ‘secondary’ purpose. In this case, they act as a store for defence molecules.

How?

How?Sinigrin is stored in mustard seed (like those shown left) and it provides the plant with a defence against being eaten by herbivores.

No, it is harmless by itself. But when an animal or insect chews a mustard seed, plant-cell walls are opened, sinigrin is released and comes into contact with the plant enzyme myrosinase. This enzyme catalyses the breakdown of sinigrin into its constituent molecules, which include allyl isothiocyanate (3-isothiocyanato-1-propene, abbreviated to AITC).

Ah! Allyl isothiocyanate! At last!

Ah! Allyl isothiocyanate! At last!Yes. This is the chemical that actually acts as a repellent. It is an oily substance, with quite a pungent smell. It is a defence mechanism to stop herbivores from eating the plant, by irritating nerve fibres in the insect. Plants make all sorts of molecules to ward off insects, including caffeine, nicotine from the tobacco plant (MOTM August 2001) and cocaine from the coca plant (MOTM Feb 2016). Our response to mustard, like sneezing, is one of the responses sent from the brain to this chemical. It makes sense that you should never let your pets eat any left-over mustard (e.g. on hot-dogs) because not only will they probably not like the pungent smell and taste, it may even be poisonous to them - especially dogs.

The allyl isothiocyanate derived from sinigrin in mustard seeds activates receptors in the tongue.

The body contains certain nerve cells, known as receptors, which are sensitive to certain stimuli, such as temperature and pain, and also to certain molecules, causing messages to be sent to the brain. Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) cation channels are a group of such receptors that are present in cell membranes which, when activated, permit the flow of ions across the membrane and instigate the signal. Sometimes these receptors can become fooled by a molecule which, by chance, has the correct shape to trigger the receptor, so the receptor sends a false signal to the brain.

The best known of these channels is the TRPV1 channel, which is activated both by temperatures above 42°C, and by the molecule capsaicin (MOTM April 2001). Capsaicin is the chemical responsible for the ‘heat’ we associate with chilli peppers (the TRPV1 channel is popularly known as the ‘capsaicin receptor’). The brain gets the same signal sent to it whether it senses ‘heat’ or the cell’s response to capsaicin, which is why chilli (and curries) seem ‘hot’. Similarly, the TRPM8 channel is activated both by cold temperatures and by menthol (MOTM August 2007). Hence menthol seems ‘cool’. Another receptor, TRPA1, is also sensitive to ‘cool’ temperatures, but it has a second job - it also senses pain (e.g. if you bite your tongue). It, too, can be fooled by molecules with the correct shape, but the signal it sends, 'cool' or 'pain', depends upon the molecule that triggers it. Non-electrophiles (e.g. thymol and menthol) bind to TRPA1 in such a way that it sends a 'cool' signal to the brain. But molecules such as AITC bind covalently to TRPA1, and trick it into sending the 'pain' signal.

A possible mechanism for allyl isothiocyanate to bind to cysteine residues in the ion channel of the TRPA1 receptor.

The situation with AITC is even more complicated because it also binds to the TRPV1 channel (capsaicin receptor) sending a 'hot' signal to the brain at the same time. So when your tongue tastes AITC, the brain recieves two signals from 2 receptors, 'hot' and 'pain'.

How the 'mustard receptor' works. (A) Mustard is eaten and (B) tasted by the tongue. (C) The allyl isothiocyanate molecules bind to both the TRPA1 and the TRPV1 receptors in the tongue, which send 'pain' and 'hot' signals, respectively, via nerves (D), to the brain (E). The brain then thinks the mustard tastes both 'hot' and 'painful'.

[Image: Modified from one in Harvard University blog]

No, you can make it in the laboratory – it was first reported in 1870. One method uses a (pseudo)halide-exchange reaction.

CH2=CHCH2Cl + KSCN  CH2=CHCH2NCS + KCl

CH2=CHCH2NCS + KCl

Another route uses addition of sulfur to an isocyanide, using traces of a selenium catalyst.

CH2=CHNC + S  CH2=CHCH2NCS

CH2=CHCH2NCS

You can also obtain it by distilling mustard seeds.

The chemical is also released by horseradish and by the so-called ‘Japanese horseradish’, wasabi, an indispensable accompaniment to sushi.

|

|

| White mustard plant (Sinapis alba) [Photo: Ariel Palmon, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

Garlic mustard plant (Alliaria petiolata) [Photo: O. Pichard, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

|

|

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) [Photo: Pethan, GNU Free Documentation License, via Wikimedia Commons] |

Wasabi (Wasabia japonica) [Photo: Qwert1234, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

A number of isothiocyanates are found in plants of the Brassica family. Sinalbin is a glucosinolate in white mustard. This can act as a source of 4-hydroxybenzyl isothiocyanate.

|

|

| Sinalbin | 4-hydroxybenzyl isothiocyanate |

The Eastern Hemisphere mustard plant Alliaria petiolata (a.k.a. garlic mustard) is a source of benzyl isothiocyanate.

|

| Benzylisothiocyanate |

It looks as if it was enjoyed in ancient China. Certainly the Romans and Greeks used it 2000 years ago, and the Romans brought it to Gaul, a.k.a. France, where it was made widely in the Middle Ages, not least because it was cheaper than pepper. The word moutarde was introduced into the French language in the 13th century, by which time mustard production was established at Dijon. In Norwich (UK), Jeremiah Colman marketed Colman’s Mustard from 1814. And this was the origin of the phrase 'to cut the mustard'.

Really?

Really?Yes, that phrase means to come up to standard, usually in the negative, i.e. something that's dysfunctional does not cut the mustard. It came about when mustard was one of the main crops in East Anglia, UK. The plants were cut by hand with scythes, in the same way as corn. Because the plants could grow up to six-feet high, harvesting them was very arduous work, requiring extremely sharp tools. If the tools were blunt, they simply "would not cut the mustard".

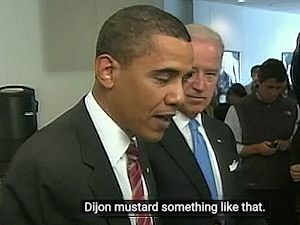

And then there was 'Dijongate'.

The worst scandal of the Obama presidency. In May 2009, the then-President expressed a preference for Dijon mustard over ketchup on his cheeseburger at Ray's Hell Burger in Arlington, Va. This was interpreted by Fox News as being anti-American, and they went ballistic!

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.23618640]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.23618640]