![]()

Androstenone

The pig pheromone that can stop your dog barking

![]()

Paul May

University of Bristol

![]()

Molecule of the Month - January 2023

Also available: JSMol version.

![]()

|

AndrostenoneThe pig pheromone that can stop your dog barking

Paul May

Molecule of the Month - January 2023

|

|

But it’s been shown by experiment. There’s even a scientific word for this phenomena, interomone.

A pheromone is a signalling chemical produced by a given species that affects the behaviour or physiology of that species. They act a bit like hormones, except that they work outside of the body. There are many types of pheromone which trigger insects or animals to follow a trail for food, run away from danger, or prepare for mating.

Some examples of insect sex pheromone molecules.

[Image: E. Jacquin-Joly, A.T. Groot, Comparative Reproduction, in Encyclopedia of Reproduction, 2nd edition, 6, Elsevier, 2018]

So pheremones affect the same type of creature?Yes, but there are other signalling molecules that affect a different type of creature than the one emitting it. An allomone is a molecule produced by one species that affects the behaviour of a member of another species, but this only benefits the emitter but not the receiver. For instance, when in the presence of ants, some beetles and cockroaches emit a chemical which is identical to the ant's alarm pheromone. When the ants detect this, they immediately return to their nest until the ‘bad smell’ goes away. This allows the beetle to run away and escape being eaten by the ants. And there’s the opposite of an allomone called a kairomone, which benefits the receiver but harms the emitter. This often occurs because a predator has learnt to detect the pheromone of its prey, such that releasing the pheromone for its intended purpose (e.g. to attract a mate) instead attracts a predator. |

A fanning honeybee releasing pheromone to entice a swarm into an empty hive. [Image: Pollinator, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

And combining the two, we have synomones, which benefit both the emitter and receiver. For example, when pine trees are damaged by beetles they often emit terpenoid molecules. These attract parasitic wasps that attack the beetles and lay eggs inside them. Thus, the wasp finds a suitable host for its eggs, and the tree’s beetle problem is controlled.

This the remaining type of pheromone – defined as a substance emitted from one species that changes the behaviour or physiology of another species without needing to benefit or harm the emitter or the receiver.

There seems to be no biological reason for this, except coincidence. By chance, the emitted molecule may be similar to an existing pheromone for another species and so cause an unexpected reaction.

Yes, although catnip (nepalactone) is not a pheromone, as such. But it is a molecule emitted from a plant that affects the behaviour of cats, making them appear 'stoned’ (see MOTM for March 2017)

|

Androstenone (5α-androst-16-en-3-one) |

Yes, it was actually the first pheromone to be discovered from mammals – all the previous ones had been from insects.

Male pigs, or boars. It is found in high concentrations in their saliva. If a nearby female pig that is in heat inhales this scent, the sow immediately assumes the ‘mating stance’.

Does it have the same effect on humans?

Does it have the same effect on humans?Androstenone also has been suggested to act upon humans as an aphrodisiac, but there is no real scientific data to support this claim. Indeed, although it is reported to have an unpleasant sweaty urine-like smell, or a woody smell, or even a pleasant floral vanilla-like smell, in small amounts the odour is almost undetectable by most people. But this hasn’t stopped companies trying to market ‘love potions’ containing androstenone which they claim increases the libido of women and makes men more attractive.

Of course not – it’s just the usual case of salesmen not letting the facts get in the way of a making a profit from gullible people.

Yes, it is found in 'Boarmate', a commercial product sold to pig farmers to test sows for artificial insemination. The farmer sprays this near the sow, and if they assume the mating position then they are fertile and ready for insemination.

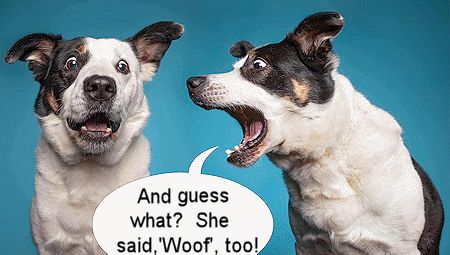

But you say it affects dogs, too?

But you say it affects dogs, too?Yes, this was the unexpected discovery, made by John McGlone of Texas Tech University in 2014. One day, McGlone’s own pet dog was barking excessively, but when androstenone was sprayed nearby, the barking suddenly stopped. Properly controlled experiments were then performed where dogs were exposed to a loud noise that would normally frighten or excite them, while being sprayed with an androstenone aerosol. The androstenone was found to be far more effective at calming the dogs compared to a control experiment using alcohol spray and noise alone. So, this boar pheromone spray can be used to control the behaviour of unruly or over-exuberant dogs. It has now been developed into various commercial aerosol sprays (see photo, right), which are available as a dog-training tool.

There’s some evidence it also works on horses, calming them down and inducing them to be more accepting of general management and training.

No-one really knows at the moment. But research is continuing to identify more interomone molecules that might help manage the behaviour of other animals – or even humans!

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.21258669]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.21258669]