![]()

Narcan (Naloxone)

The 'miracle' antidote for opiate overdoses

![]()

![]()

Molecule of the Month November 2018

Also available: HTML version.

![]()

|

Narcan (Naloxone)The 'miracle' antidote for opiate overdoses

Molecule of the Month November 2018

|

|

Why did you call it a miracle?Well, narcan has been called that due to its almost immediate effects on overdose patients that are on the verge of death. What does it do?Imagine the situation that most paramedics are familiar with, and which appears in almost every TV cop show: an ambulance has been called to deal with a drug overdose, and when they get there the victim is lying unconscious as a result of taking an opioid drug. The drug could be an ilegal one, such as heroin, or more, recently, a legal prescribed opioid painkiller, such as oxycodone (oxycontin) or codeine (see MOTM Dec 2015). The overdose may be deliberate, i.e. an attempted suicide, or more often, accidental, as the victim simply underestimated the potency of the drug and took too much. Until about a decade ago, there was actually rather little the paramedics could do. They would rush the patient to hospital and put them on a saline drip to keep them hydrated, but there was no way to flush the drug out of the patient's system or prevent it doing any further harm, and so the patient would very often continue to deteriorate, and then die, usually of respiratory failure or cardiac arrest. And that's now changed?Yes, as a result of narcan becoming available to paramedics. One simple injection of this drug, and the effects of the opioid are almost instantaneously neutralised, and often the patient recovers consciousness within a few minutes. There are many videos on the web showing this 'miraculous' recovery with overdose victims, both human and animal. |

|

Your body has receptor sites which are meant to bind natural painkilling molecules called endorphins. Endorphins are opiate-like molecules which are the body's natural painlkillers - they are released immediately following an injury, where they bind to the receptors, switching them on. The receptors send signals to the brain blocking the perception of pain, and this can provide enough pain relief to allow a person to escape from a harmful situation. For example, an antelope trying to escape from a lion may still be able to run away despite having a broken leg, because the release of endorphins means it does not feel the pain. However, when the immediate threat of danger has passed, endorphin levels decrease and the pain will return. If the endorphin levels remained high and continued to blunt the pain, a person (or antelope) might simply ignore an injury and fail to seek help. They may even cause further harm to the injured area.

The opiate receptors attached to a brain neuron. (a) Endorphins can attach to the receptors, switching it on, and sending a signal to the neuron which blocks pain.

(b) Opiates can also attach to the same receptors, with the same pain-blocking effect. (c) Naloxone preferentially binds to the receptors, displacing the opiates, but the neuron is not activated.

However, endorphins also have unwanted side-effects - they provide pleasurable sensations and are slightly addictive. It is believed that one of the reasons why people become hooked on running or gym workouts is that the stressful activity releases endorphins, which makes the person feel great, and they become addicted to 'the burn'. Eating chocolate or other sugary foods has a similar effect; they trigger release of another opioid-like molecule in the brain - dopamine (MOTM Oct 2008) - which creates feelings of pleasure, which, in turn, makes you feel good. So good, you eat yet more chocolate...and the cycle continues.

This opioid pleasure-response is the reason why many people choose to take opioid drugs, like heroin, for recreation. As well as acting as painkillers, they also induce feelings of pleasure or euphoria - the 'high' that users crave. However, their addictive nature, and the fact that the receptors get tired of being triggered so often, means that higher and higher doses are required to get the same level of high, and therein lies the risk of overdose. In the US in the last decade, extremely potent opioid painkillers, such as oxycodone, have been prescribed by doctors (often financially incentivised by the drug manufacturers) to hundreds of thousands of patients to treat relatively minor pain symptoms. This has led to a massive epidemic in 'painkiller-addicts', who often graduate to street heroin because in some cities heroin is easier to source than oxycodone! As might be expected, the number of overdoses has skyrocketed in recent years.

'Fit in' is exactly the right description. The structure of narcan is very similar to that of opioid drugs; it has an almost identical skeleton to heroin with just a few different sidegroups. This means it fits into the body's opioid receptors like a key into a lock. In fact, it fits in so well and binds so strongly that it displaces any other molecules that might already be there, such as heroin, and then blocks access to any subsequent molecules - effectively turning off the receptors.

|

|

| Narcan (Naloxone) | Heroin |

| Comparison of the structures of narcan and heroin. The commonalities in structure are shown in red. | |

In 2017 it was reported that narcan can even be used to treat overdoses from cannibinoids, such as those found in patients using some of the more highly concentrated form of cannibis resin (e.g. 'skunk') that are on the streets today.

True, not only is it not addictive, it doesn't have any euphoric effects either, so its almost the perfect antidote for an overdose. Also, it has very few side-effects, and works almost instantly. Within a minute or so of administering narcan, the patient can wake up and become coherent. With all the opiate receptors blocked with narcan, any excess opiate drugs still in their bodies can no longer bind to anything, so are rendered harmless. They are eventually either metabolised or excreted. Nowadays, almost all paramedics and ambulance personnel carry narcan kits, and many police and fire personnel are trained how to use them.

|

|

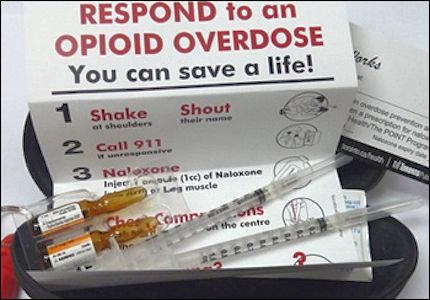

| A naloxone kit supplied to Canadian paramedics. Photo: James Heilman, MD. |

A naloxone kit with instructions. |

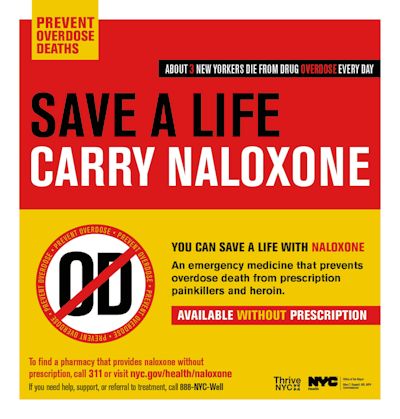

In some US states narcan is now available without prescription in Walmart - although this has been controversial.

Some policians believe that making the antidote so easily available will simply encourage people to risk trying higher doses of drugs - or even to start taking them in the first place. Nevertheless, the availability of narcan has already had a big impact, with overdose deaths rapidly dropping in those cities that employ it.

Who invented it?It was a Polish-American chemist called Jack Fishman - although his story is rather tragic. In 1961, Jack Fishman was working at a private narcotics lab in New York. His boss proposed a small structural change to oxymorphone, a morphine-based painkiller, that might treat constipation. Jack managed to synthesise the drug, but instead of making a laxative, they found the new molecule acted as an opioid antagonist - a compound that could aggressively outcompete other opioids in sticking to the brain’s receptors. They called it naloxone, later to be renamed and marketed as narcan. By the 1970's, the U.S. FDA had approved it for use in clinics to reverse the effects of medical narcotics. Morphine and diamorphine (heroin) are often used in hospitals as painkillers, but doctors sometimes got the dosage wrong, and put someone 'too far under'. Naloxone could bring back the patient rapidly and without complications. Intravenous naloxone became an antidote for heroin overdoses, and it soon became a standard treatment in emergency rooms. In 1983, the World Health Organization placed naloxone on its list of essential medicines — acknowledgement that it was safe and effective. But outside of the clinic or hospital, it was a different story. For decades, naloxone was unavailable to drug users who overdosed at home or on the street - they often died before the paramedics arrived, or before they reached hospital. A big hurdle was that US federal law required a prescription for naloxone, and that meant it could legally be dispensed only by a doctor - which wasn't much use to street addicts. Things started to change in 2001, when the state of New Mexico began a program to allow people without medical training to administer naloxone without fear of being prosecuted. By 2003, Chicago and San Francisco also began distributing take-home naloxone, but it was still unavailable across much of the U.S., including Florida. |

Dr Jack Fishman. Photo: The Rockefeller University. |

In 2004, Jack was living with his wife, Joy Stampler, and two step-children in Miami, when his stepson, Jonathan Stampler, suffered a heroin overdose. Because Florida was one of the few states that did not allow home access to naloxone, there was no way to treat Jonathan in time, and he died. His mother, Joy, is quoted as saying, “It never even occurred to us that naloxone could save Jonathan. Back then we didn’t think of naloxone as a household item. Doctors weren’t writing take-home prescriptions for it. It was hard for Jack to get naloxone, even though he invented it!”

Although Jack had invented naloxone 40 years before, he hadn't really been keeping up with its progress in medical usage. Despite naloxone being distributed to ordinary people in other states as early as 1996, Jack Fishman never knew about it. His son, Neil Fishman, said, “I didn’t know about naloxone being used to save lives outside emergency rooms until my father died. Articles started circling about the opioid epidemic and how many lives naloxone is saving." If the famiy had known - and had lived in a different state - Jonathan might have been saved. While the world enthused about the lifesaving properties of this amazing drug, its inventor remained in obscurity. Only after his death in 2013, did the New York Times and other papers start to run articles connecting naloxone to Jack Fishman.

But at least Fishman made a fortune out of his invention, didn't he?

But at least Fishman made a fortune out of his invention, didn't he?No. Although he did patent the invention in 1961, it took such a long time for the drug to become accepted that the patent expired. The cost of acquiring another was too much and so he did not reapply, and this allowed the rights to his invention to be bought up by large pharmaceutical companies, who have profited ever since.

Most US states now have broadened laws regarding the usage and adminstering of naloxone by lay-people and widened its availability without prescription. However, more than 10 still do not, although there are concerted efforts to change this, and poster campaigns to promote public awareness. Canada, Australia and the UK have also allowed easier access to naloxone, and have distributed it to selected emergency service personnel - although it's not always available over the counter yet.

Fishman's tragic story does have a happier end. He died not realising the true impact of his invention, or the huge number of second chances it gave to those addicted to opiates, and he remains an unsung hero of modern medicine. But his legacy continues with his family, who have helped changed the laws on naloxone access in Maine, and who are campaigning on behalf of greater naloxone availability.

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.5972440]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.5972440]