![]()

'Spice'

(AMB-FUBINACA, JWH-018, and New Psychoactive Substances (NPS))

The ‘Zombie Drug’

![]()

Simon Cotton

University of Birmingham

![]()

Molecule of the Month October 2023

Also available: HTML version.

![]()

|

'Spice'(AMB-FUBINACA, JWH-018, and New Psychoactive Substances (NPS))The ‘Zombie Drug’

Simon Cotton

Molecule of the Month October 2023

|

|

No - and nothing to do with things like cloves or nutmeg either.

No, not that either.

Yes. It's a form of synthetic cannabinoid. But because it is significantly more potent than cannabis, its use can have severe debilitating effects and can leave users in a zombie-like state. In 2018, Marc Jones, the Police and Crime Commissioner for Lincolnshire, said, “Users are increasingly seen slumped on the streets in a state of semi-consciousness, often passed out, sometimes aggressive and always highly unpredictable. This is not cannabis - it really is a very different animal and we need to eradicate it from our streets. The wide-scale abuse of these debilitating drugs within towns, cities and even villages across the UK is one of the most severe public health issue we have faced in decades, and presently the response to tackle the issue is woefully inadequate."

So-called ‘spice zombies’ can be seen standing like statues or lying frozen on the ground as the effects of this cheap synthetic drug take hold of their bodies.

It’s a long story.

Ha! Let’s start by looking at marijuana. It has been used as a drug for thousands of years. It is obtained from the Indian hemp plant, usually Cannabis sativa. As the plant is dried out the psychoactive substance delta-9-THC (Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, Δ9-THC) is formed (MOTM April 2019).

|

|

| Δ9-THC |

When cannabis is smoked, Δ9-THC is taken from the lungs to the brain – via the blood. It acts on a ‘cannabinoid receptor’ found in the human nervous system, known as CB1 (which stands for Cannabinoid receptor type 1), leading to the hallucinogenic effects. This receptor binds both the endocannabinoids that the body makes, as well as ones found in plants (like Δ9-THC) and synthetic cannabinoids. During the past half century, scientists started to investigate synthetic cannabinoids, molecules that bind to the body’s cannabinoid receptors, but which do not occur in nature.

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) were never meant for people to take them as drugs; they were made to study possible medicinal uses of cannabis. They attach to the same bodily receptors, but bind more strongly than THC does. There is no published safety data for the compounds, and little is known about how they affect people. Some of these compounds, known as ‘classical cannabinoids’ like HU-210 - which is said to be 100 times more potent than Δ9-THC and has since become an abused drug - were first made back in the 1980s.

|

|

| HU-210 |

They are known as ‘classical cannabinoids’ because their structure resembles Δ9-THC.

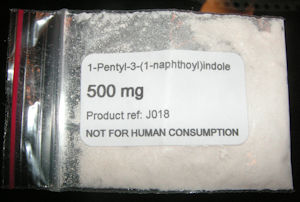

A group of napthaloylindole compounds came on the scene. The best-known of these is known as JWH-018, sold in powder form as shown in the photo below.

JWH-018 sounds like a catalogue number

JWH-018 sounds like a catalogue numberIt is a handy reference tag for it. Another one is AM-678. But when you know its real chemical name is 1-pentyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole or naphthalen-1-yl-(1-pentylindol-3-yl)methanone, then a bit of shorthand makes sense.

Let’s move to the early 1990s. The cannabinoid receptor had recently been discovered. John W. Huffman, professor of chemistry at Clemson University, South Carolina, USA, wanted to find out more about how it worked, so he started synthesising new molecules in order to see how they interacted with the receptor and thus discover how it worked. Already it was known that molecules did not have to look like Δ9-THC in order to bind to the receptor. So his research group went out to make hundreds of new molecules, using what were quite straightforward syntheses. The chemical names were a bit cumbersome, so for ease of reference he gave them tags, like JWH-018. Then they wrote up their research for the wider scientific community, in a series of research papers in the open literature, like you do.

Scientists regularly comb the scientific literature to inform their research. Some other readers do, if they see an opportunity to get rich.

Move ahead, to 2008. German forensic chemists came across JWH-018; it had been sprayed onto plant leaves – to make it look ‘natural’ - and sold under the name of ‘Spice’. Others of these ‘synthetic cannabinoids’ were similarly to be (ab)used; these molecules get their name because they interact with the ‘Cannabinoid receptor’ in the brain - not because they are plant-produced. And so Huffman realised that his research was being abused. When scientists want their research to be accessible to people on the streets, this is not what they mean, nor by ‘reaching an international audience’.

Compounds like JWH-018 – and others that have followed them - are relatively easy to make by underground chemists, throughout the world. Some of these laboratories are in the Far East, but others are ‘nearer home’. Many of these chemicals have very different structures to those pioneered by Huffman. JWH-018 has been an ingredient in products with names like “Herbal spice” and “Herbal Gold”; it is reported to be a very potent agonist for the CB1 receptor (in other words, it binds strongly) and to have 4 times the potency of THC; it is said to give a marijuana-like “buzz” similar to cannabis when smoked.

JWH-018 has been banned across much of Europe. The problem is that when one substance is banned, then the synthetic chemists make a slightly different one, as these new substances are not covered by existing legislation.

|

|

| JWH-018 | JWH-073 |

JWH-073 (naphthalen-1-yl-(1-butylindol-3-yl)methanone) was marketed as a “fertiliser" product called "Forest Humus" as well as JWH-250 (2-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-(1-pentylindol-3-yl)ethanone) and JWH-200 ((1-(2-morpholin-4-ylethyl)indol-3-yl)-naphthalen-1-ylmethanone) in “herbal” smoking blends.

|

|

| JWH-250 | JWH-200 |

They have a deal in common with ‘Spice’; they emerged onto the street market at around the same time, in 2008-2010. They pretended to be what they weren’t. The first one of them, methylcathinone, became known as Mephedrone. It does not occur in nature; though it is ‘man-made’, it has a similar structure to cathinone (MOTM Sept 2018), the main psychoactive molecule found in khat, the leaves of an East African evergreen shrub (Catha edulis), widely chewed as a stimulant by Yemenis and others (e.g. Somalis, Ethiopians and Kenyans). Cathinone (and Mephedrone) has a structure closely related to methamphetamine (MOTM March 2007), and is generally regarded as a Schedule I drug. Mephedrone was described by sellers as "plant food"; this is not true, these molecules are nothing of the kind, as they do not occur in nature. In the UK it was classified as a class-B drug with effect from 16 April 2010.

These molecules have structures very different to JWH-018 and its relatives, and do not affect the cannabinoid receptor, so, no, they are not part of the ‘Spice’ family.

|

|

| Cathinone | Mephedrone |

Some people went on looking for new drugs that could be pushed. They hit on a new type of molecule, originally made by Pfizer as a potential drug, which was patented in 2009, but never taken further. AMB-FUBINACA (a.k.a. MMB-FUBINACA) and related molecules proved to be cannabinoids that were active agonists for the CB1 receptor. Chemically they are classed as indole carboxamides.

|

|

| ADB-FUBINACA | AMB-FUBINACA |

Within a few years, these molecules were popping up all over the world. ADB-FUBINACA was first detected in Japan in 2013; AMB/MMB-FUBINACA was first detected in Sweden in 2015; it was marketed in Colorado in 2017 as ‘Black Mamba’. On July 12th 2016, New York’s Emergency Medical Services were called to attend upon a ‘mass casualty event’ in Brooklyn. Of 33 casualties, 18 were hospitalised; all 33 were described by watchers as ‘Zombie-like’. AMB-FUBINACA was identified in a sample of “AK-47 24 karat gold” smoked by one of the patients, whilst a metabolite of this drug was detected in blood and urine samples taken from eight of the patients (none of the common drugs of abuse were found). In the Southern Hemisphere, some 20 deaths were attributed to AMB-FUBINACA during 2017 alone in New Zealand.

Where is this stuff produced?Some is made abroad, then shipped into the UK, but in several cases that have been brought to court, the precursor chemicals were brought in from China, then used to make the ‘Spice’ in ordinary homes. As in a high-rise flat in Oldham, Manchester, in a case that came to court in 2018 – the four perpetuators received prison sentences totalling 19 years. They seem to have carried out their syntheses, using chemicals like sulfuric acid and diethyl ether, without prior training. When you think of what could have happened, bearing in mind reports of fires and explosions in American trailer parks making methamphetamine, this is worrying, not to mention the ‘quality control’. |

[Image: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons] |

Cannabis buds sold on the street may be laced with Spice. [Image: Evan-Amos, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons] |

What do you mean?These substances, sold for human consumption by pushers, have never been tested on animals, let alone humans. When you get a packet of a medication from a pharmacy, the labelling reassures you that it has been developed by professionals and rigorously tested in an approved laboratory. Users do not know if they are getting the same psychoactive chemical every day, let alone the same dose. It’s Russian Roulette, but without the gun. Often, dealers may lace standard cannabis with Spice, with or without the user's knowledge or permission. |

But what’s the problem?

But what’s the problem? ‘Spice’ reaches a wide range of ‘consumers’. UK prisons are among them. People have found ways of smuggling drugs in, including synthetic cannabinoids. Drug use in prisons is not a new thing. Prisoners have time on their hands, and doing drugs is one way to cope with this. It is believed that there’s a higher percentage of synthetic cannabinoid users in prisons than in the country’s population as a whole. One reason is that synthetic cannabinoids are believed to be undetectable in drug tests.

It seems not. Some get smuggled in by visitors, who use parts of their anatomy that do not, er, get searched. It is reported that they get put inside tennis balls, which are bounced in, over the walls of the jail. It is possible that a member of staff might be bribed. One unexpected method is that the drug gets dissolved in a solvent, which can be absorbed by writing paper, then used for writing a letter - either from a friend or prison visitor, or maybe a ‘lawyer’s letter’; then once in the jail, the drug can be dissolved out of the paper and consumed.

Surely it is just like taking cannabis?

Surely it is just like taking cannabis? Synthetic cannabinoids are reckoned to be more potent than ‘natural’ cannabis, for one thing. Another worrying thing is that other, more potent, drugs get cut with synthetic cannabinoids. This includes fentanyl (MOTM March 2015), which is about 100 times stronger than morphine – such mixtures have been linked with a number of deaths. Of course, other fentanyl derivatives, like carfentanil (MOTM December 2018) are even more potent. So people do not know the safe dose of what they are taking on that particular day. What people are being offered can lead to a whole host of differing health issues, including intoxication, seizures, psychotic episodes, heart and kidney problems, and also death. Analysis of 129 ‘unnatural’ deaths in UK prisons between 2015 and 2020 showed that 48% involved synthetic cannabinoids.

Enough said.

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.23992941]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.23992941]