Sam the muppet bald eagle

doesn't look happy!

![]()

Aetokthonotoxin

The mystery toxin responsible

for ‘kamikaze bird syndrome’

![]()

![]()

Molecule of the Month August 2022

Also available: HTML version.

![]()

Sam the muppet bald eagle doesn't look happy! |

AetokthonotoxinThe mystery toxin responsible

|

|

Over the past 30 years, hundreds of birds have died in mysterious circumstances around American lakes. The birds were seen to behave very strangely just before they died. Some birds were observed to (deliberately?) fly straight into objects, such as rocks, walls and trees, killing themselves 'kamikaze style'. Ducks were seen swimming in circles or on their backs, and others had difficulty walking. Other birds developed head tremors, drooping wings, and seemed unresponsive to what was happening around them.

|

DeGray Dam and Lake on the Caddo River in Hot Spring County, Arkansas. [Photo: Alfred Dulaney, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons] |

When did this start?

When did this start?Relatively recently. In the winter of 1994 the carcasses of 29 bald eagles were found near Degray Lake in Arkasas, USA. Over the next 4 years, many more birds died after exhibiting crazy behaviour, including 70 more eagles, American coots and various species of ducks. And they were found at 10 different sites all across America. As the years went by, the number of strange bird deaths continued to increase.

That was the question that puzzled scientists for a number of years. There were some clues. All of the dead birds were found on or near man-made water reservoirs with abundant aquatic vegetation, such as DeGray Lake where the story started. Focus turned to the sediment at the bottom of the lakes, to see if any poisons had contaminated it. But no harmful substances were found. The lake water also seemed innocent, although the levels of bromide ions were a bit higher than normal.

Another clue was that the bird deaths seemed to be seasonal, only occurring during certain months. This suggested the poison, probably a type of neurotoxin, was somehow linked to the environment and growth of the plants in the lakes.

Good point! Medical examination of the dead birds discovered lesions in their brains and spinal cords. The disease was named Avian Vacuolar Myelinopathy (AVM), and this damage to the brain and nerves was the cause of the birds’ erratic behaviour.

The search for the toxin continued for another 25 years, and was finally reported in a paper in Science in 2021. It turned out to be a neurotoxin produced by a cyanobacterium Aetokthonos hydrillicola, and so the poison was called Aetokthonotoxin (AETX).

|

| |

| AETX | Collecting Hydrilla verticillata from Lake Seminole, FL, where they have overrun the lake and begun to choke it. [Photo: Stephen Ausmus, USDA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons] |

This cyanobacterium gets its name because it grows very well on the aquatic plant waterthyme (Hydrilla verticillate), and at certain times of the year can cover up to 90% of the surface of the plant's leaves. Hydrilla plants were brought to the United States in the 1950's as an aquarium plant, but then were released into the environment when discarded aquarium contents were dumped into a Florida swamp. They have since become an invasive species which often take over and choke aquatic systems, and do particularly well in man-made lakes and reservoirs.

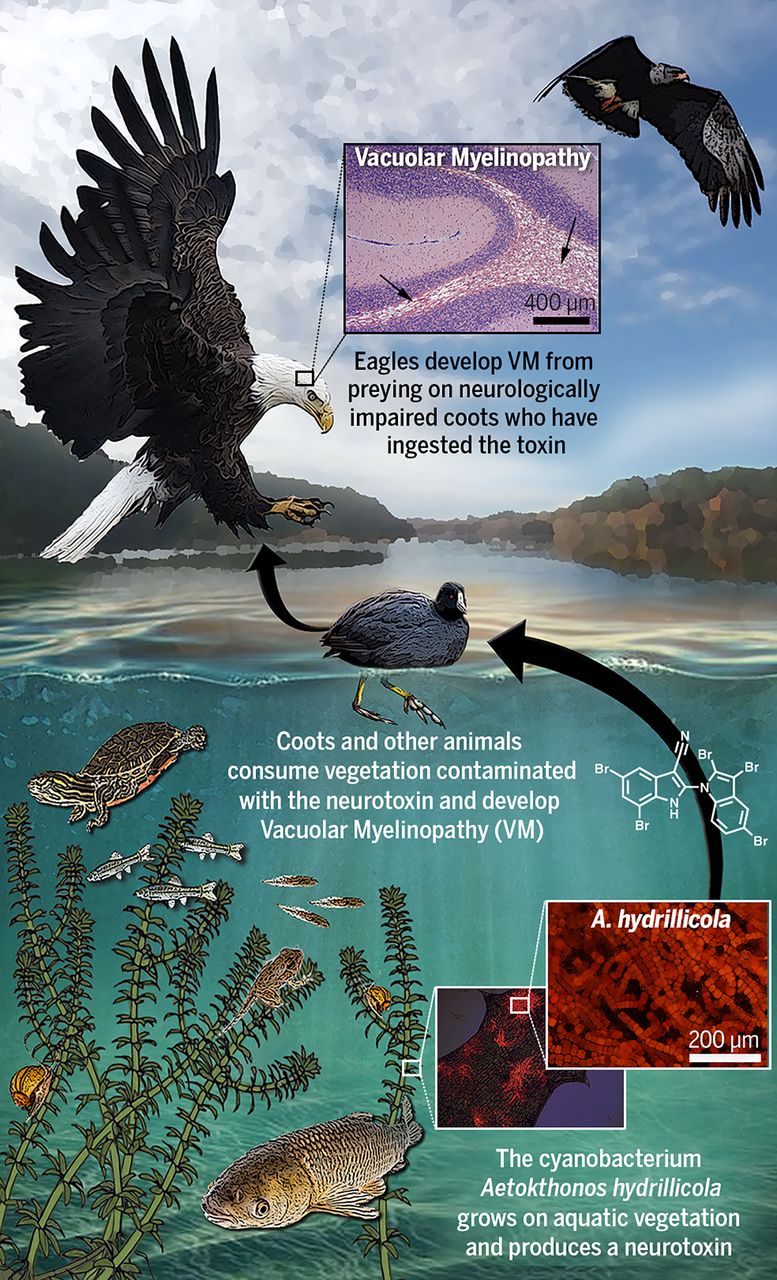

But they do eat ducks and fish, and these eat plants. In fact, AETX affects fish and waterfowl which feed on hydrilla covered in the poisonous cyanobacteria. The AETX then makes it way up the food-chain to predator birds such as eagles.

How the AETX toxin travels up the food-chain from cyanobacteria to the bald eagle.

[Image: W. H. Majoros. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons]

This is because the biosynthesis of AETX requires a rather unusual set of circumstances. First, there needs to be a water environment with lots of hydrilla plants present. Second, these plants need to be heavily colonised by the cyanobacteria. Finally, the cyanobacteria biosynthesise AETX from tryptophan (MOTM June 2002), but to do so they require bromide ions to be present in the water as a pollutant.

Nowadays, the main anthropogenic sources of bromide include coal-fired power plants, water-treatment plants, flame retardants, agricultural herbicides and biocides, municipal waste incinerators, water leaching from landfill sites, road de-icers, and waste pharmaceuticals. These bromine-containing pollutants make their way into the rivers and from there into lakes, where the bromide concentration can become significant.

So, to produce AETX, you need three ingredients to be present: the correct plant, the special bacterium and also bromide-contaminated water. It is worth noting that two of those are a result of negligent human activity. Has anything similar been seen anywhere else besides America?Yes, there's a village in India called Jatinga, near Assam, which is known as the place 'where birds commit suicide'. Every year between September and November, 40 species of local and migratory birds are seen to fly fast and hit trees, seemingly deliberately. This has been going on since 1910, so aetokthonotoxin seems unlikely to be the cause - although a related neurotoxin is possible. The village is isolated for many months of the year, and has lakes and waterways that would be ideal for build up of bromides. But it's also likely that the birds simply cannot see clearly in the dark, damp, foggy weather prevalent in the area, and so accidentally collide with objects. However, the exact cause still hasn't been found. Is there a danger to animals – or to humans?Possibly. AETX and AVM are already a threat to multiple bird species. Experiments have shown that other creatures, amphibians, reptiles, and fish, that eat the affected plants, can also be poisoned and die. We still do not know whether animals and humans that consume fish and waterbirds from these contaminated reservoirs will be affected, and research is desperately needed to find out. |

Bald eagle. [Photo: Andy Morffew, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.19233513]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.19233513]