|

CARFENTANIL

(or CARFENTANYL)

The tranquiliser for wild game that is

the most powerful commercially available opioid.

Simon Cotton

University of Birmingham

Molecule of the Month December 2018

Also available: HTML version.

|

|

Is that anything like fentanyl?

Is that anything like fentanyl?

Yes, fentanyl (MOTM March 2015), the parent drug of the family, was originally made in Belgium in 1960 by a team at Janssen Pharmaceutica, led by Dr Paul Janssen (photo, right), who was trying to devise better analgesics with fewer side effects and higher safety margins. They were looking for molecules that were more lipid-soluble, so they would get into the central nervous system faster and so give more rapid analgesic action; other derivatives followed, including carfentanil in 1974. However, carfentanil is a good 100 times stronger than fentanyl. And fentanyl is 100 times stronger than morphine, which makes carfentanil the most potent commercially available opioid. In fact, it is so toxic that it has no approved use in humans.

|

|

| Fentanyl |

Carfentanil |

|

|

Why is it so much stronger than fentanyl and morphine?

Introducing a sidechain into a drug molecule often leads to a big change in its strength. Just over half a century ago, pharmaceutical chemists tweaked the morphine molecule (MOTM Nov 2004) and produced etorphine (MOTM May 2002). Etorphine is around 1000 times as potent as morphine, with an LD50 estimated to be around 30 μg for humans. Such small changes in molecules must make them ‘fit’ the body’s receptor better, and so increase their potency.

What use is a powerful medicine like carfentanil?

Like etorphine, carfentanil has been widely used by vets in particular to anaesthetise large animals like elephants, rhinos or ‘big cats’; it is the active ingredient in Wildnil. No one knows the lethal dose of carfentanil to humans, but it must be similar to that of etorphine, or less, in the region of 20 μg.

How do vets use it?

Well, animals don’t roll up their sleeves ready for the injection; the vets use ‘darts’ containing a solution of the desired sedative, the darts are essentially syringes fitted with a hypodermic needle and are shot out of a gun by compressed gas. The darts are stabilised by a ‘flight’, a tuft of fibre, which makes it fly straight at the animal.

That makes it sound very simple.

It isn't. Because carfentanil (or etorphine) is so toxic, it presents a danger to any human using it, so quite a few precautions must be in place. When carfentanil is used by vets – from preparing the darts until after their use - they must work in groups of at least two, and wear whole-face covering as well as latex gloves, plus clothing that covers the whole body (i.e. not T-shirts and shorts). Several vials of the antidote naloxone (MOTM November 2018) have to be carried (one is not enough). There is even a case for using a ‘glove box’ – like an infant incubator fitted with latex gloves – for the process of making up the darts and loading the gun. And, of course, needles and syringes must not be thrown away but disposed of safely after use.

This sounds a bit extreme, are these precautions really needed?

Yes, as people can get injected accidentally, whilst carfentanil can get introduced into the body by contact with broken skin or a cut, as well as though mucous membranes, like the eyes, or through inhaling dust. Carfentanil is so toxic that some people worry that it could be absorbed through the skin.

In one case reported in 2010, a vet was trying to sedate a wild elk, and had to remove a dart from a tree-trunk, in the process getting splashed in the face, eyes and mouth. Despite immediately washing his face with water, he started to feel drowsy within a couple of minutes, and his colleagues had to administer naltrexone (the ‘reversal agent’ used with animals, as naloxone was not available) whereupon he largely recovered by the time he arrived at A&E an hour later.

OK, but these are extreme cases, surely there is no problem?

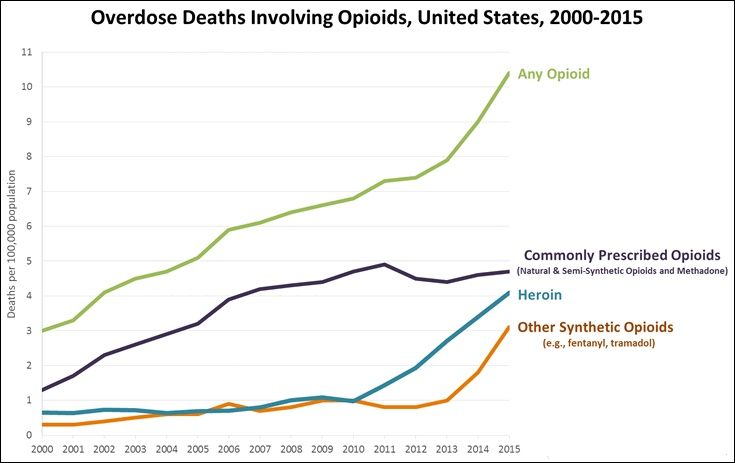

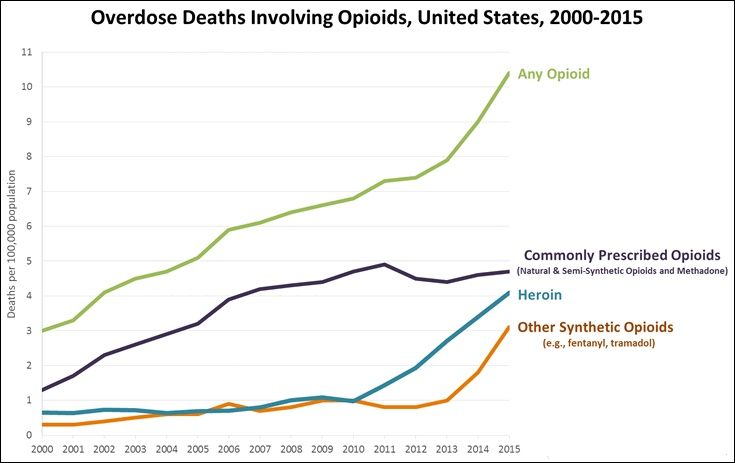

Sadly not. The painkiller crisis in the USA has mushroomed since oxycontin (MOTM Dec 2015) arrived on the market in the mid-1990s, but fentanyl abuse goes further back, to the late 1970s, when it was one of the drugs, along with high-purity heroin, known on the streets as ‘China White’. Today, ‘China White’ can mean heroin cut with fentanyl. It has become a big problem in the 21st century, but carfentanil only seems to have become a drug of abuse since around 2016. In the latter part of that year carfentanil was identified in around 400 seizures by police. Most of these were in Ohio, centred upon Cincinnati. Subsequently cases have cropped up in Minneapolis, Chicago, New York, and other centres. Carfentanil has also been detected in blood samples from ‘under-the-influence’ drivers. It’s been reported that from 1 September 2016 to 1 January 2017, carfentanil was identified in 262 post-mortem blood specimens in the USA. Carfentanil has even reached the UK.

Where’s it coming from?

One day in June 2016 a bunch of Mounties (Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers) wearing respirators, facemasks and hazmat suits, with tape covering the joins, swooped on a consignment from China of printer accessories at the airport in Vancouver. It said ‘printer accessories’ on the box, but the blue cartridges labelled as ink for HP printers contained a kilogram of carfentanil. The police arrested a man in Calgary for whom the order was destined.

|

|

So China’s the source?

Certainly one of them, it seems. They used to refer to inhaling the vapour from hot solution heroin or opium as ‘chasing the dragon’. Carfentanil makes you think of the movie ‘Enter the Dragon’, with Bruce Lee. A reason for this is that in the USA fentanyl and derivatives like carfentanil have long been Schedule II drugs, whilst drugs like these were unregulated in China until 2016. After that, the DEA persuaded the Chinese authorities to act and regulations came into force in March 2017. Of course, ‘underground’ laboratories can continue to supply illicit drugs via the ‘Dark Web’, operating from fake addresses.

Leading to…

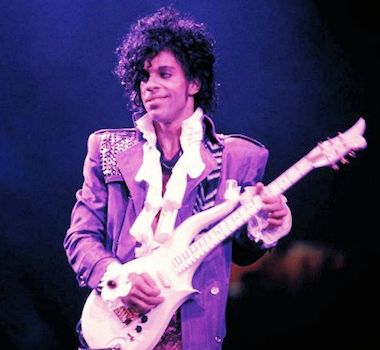

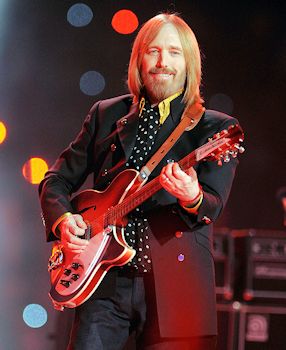

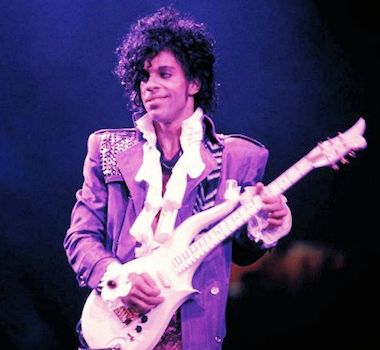

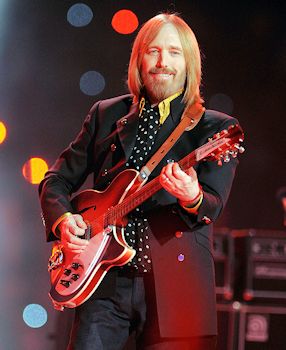

Users may decide that mixing a fentanyl derivative with heroin will give them a more intense ‘rush’, but for many the consequence has been death. Other addicts have been unaware that their heroin has been cut with a more toxic drug, and have received a lethal overdose in consequence. People have also simply taken accidental overdoses of fentanyl thinking they were milder painkillers, and died as a result. For example, in April 2016 the pop star Prince died when he took fentanyl-based painkillers thinking they were the much milder Vicodin). In addition, the singer Tom Petty died in October 2017 from accidentally taking an overdose of a mixture of painkillers including fentanyl, despropionylfentanyl and acetylfentanyl.

|

|

| Prince |

Tom Petty |

And it was used in the Moscow theatre siege?

On October 23rd 2002, 40 Chechen terrorists occupied the Dubrovka Theatre in Moscow, taking around 900 people hostage. The siege was brought to a close on October 26th, when Russian authorities pumped a ‘chemical agent’ into the building’s ventilation system. The terrorists were killed by Russian special forces, but around 130 of the hostages were killed by the chemical, whose identity was not known. Subsequent analyses on urine and clothing samples from survivors showed it to contain carfentanil.

Unconscious liberated hostages are taken away in a bus from the scene near the Dubrovka Theatre in Moscow.

Russian special forces turned to carfentanil to end a standoff with Chechen separatists

using an aerosol version of the opioid.

(Photo: Dmitry Lovetsky/The Associated Press).

Remifentanyl was also identified.

|

|

| Remifentanyl |

|

Can you sum up carfentanil in a few words?

How about the phrase used by Lady Caroline Lamb to describe George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824)?

Which was?

Mad, bad, and dangerous to know!

Alternatively?

It’s the elephant tranquiliser in the room.

Bibliography

- Chapman and Hall Combined Chemical Dictionary code number BLR61-H

Fentanyl and carfentanil

- P. A. J. Janssen and G. H. P. Van Daele, U.S. Pat. No. 4179569, published Dec. 18, 1979 (synthesis of carfentanil)

- J. L. Galzi, B. Ilien, E. J. Simon, M. Goeloner and C. Hirth, Tet. Lett., 1987, 28, 401-404 (synth).

- L. P. Reiff and P. B. Sollman, U. S. Patent US 5106983 A, published 21 April 1992. (improved synthesis of carfentanil and analogues)

- D. M. Perrine, The Chemistry of Mind-Altering Drugs, Washington, American Chemical Society, 1996, pp 82-83 (early background of fentanyl and, passim, other opiates).

- D. M. Jewett, Nuc. Med. Biol., 2001, 28, 733–734 (simple synthesis of [11C] carfentanil)

- T. Wang and J. T. Berner, J. Anal. Toxicol., 2006, 30, 335-341 (analysis of carfentanil and other fentanyls in urine; MS of carfentanil)

- T. H. Stanley, T. D. Egan and H. Van Aken, Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2008, 106, 451-462. (tribute to Dr. Paul A. J. Janssen, inventor of fentanyls and much else)

- T. H. Stanley, J. of Pain, 2014, 15, 1215-1226 (‘the fentanyl story’)

- M. G. Feasel, A. Wohlfarth, J. M. Nilles, S. Pang, R. L. Kristovich and M. A. Huestis, AAPS Journal, 2016, 18, 1489-1499 (metabolism of carfentanil)

- J. F. Casale, J. R. Mallette and E. M. Guest, Forensic Chem., 2017, 3, 74–80 (IR, MS, NMR of carfentanil; analysis of illicit carfentanil)

- J. Suzuki and S. El-Haddada, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2017, 171, 107-116. (review of fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls)

- N. Misailidi, I. Papoutsis, P. Nikolaou, A. Dona, C. Spiliopoulou and S. Athanaselis,

Forensic Toxicol., 2018, 36, 12–32 (synth. of carfentanil; review of ocfentanil and carfentanil)

Carfentanil as a veterinary sedative and its use

- J. C. Haigh, L. J. Lee, and R. E. Schweinsburg, J. Wildl. Dis., 1983, 19, 140-144 (carfentanil to immobilise polar bears)

- J. R. Baker and T. J. Gatesman, Vet. Rec., 1985, 116, 208-210 (carfentanil to immobilise grey seals)

- D. E. Williams and D. H. Riedesel, Iowa State University Veterinarian, 1987, 49, 26-32 (carfentanil to immobilise wild ruminants)

- M. D. Kock and J. Berger, J. Wildl. Dis., 1987, 23, 625-633 (carfentanil to immobilise North American bison)

- B. Welsch, E. R. Jacobson, G. V. Kollias, L. Kramer, H. Gardner and C. D. Page, J. Zoo Wildl. Med., 1989, 20, 446-453 (tusk extraction in the African elephant using carfentanil)

- T. J. Kreeger and U. S. Seal, J. Wildl. Dis., 1990, 26, 561–563 (carfentanil to immobilise grey wolves)

- M. L. Shaw, J. W. Carpenter and D. E. Leith, J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 1995, 206, 833-836 (carfentanil to immobilise horses)

- T. J. Portas, Aust. Vet. J., 2004, 82, 542-549 (carfentanil to immobilise rhinoceros)

- Remote injection systems

- Sonia M. Hernandez, in Kathy W. Clarke and Cynthia M. Trim eds., Veterinary Anaesthesia (Eleventh Edition), Elsevier, 2014, pp 571-584

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/veterinary-science-and-veterinary-medicine/carfentanil

Safe handling of carfentanil

Carfentanil and the Moscow theatre siege

- P. M. Wax, C. E. Becker and S. C. Curry, Ann. Emerg. Med., 2003, 41, 700-705 (indication that carfentanyl was involved)

- J. R. Riches, R. W. Read, R. M. Black, N. J. Cooper and C. M. Timperley, J. Anal. Toxicol., 2012, 36, 647–656 (carfentanil shown to be used in Moscow theatre siege by analysis of clothing and urine)

Deaths of Prince and Tom Petty

Carfentanil binding site

- G. Subramanian, M. G. Paterlini, P. S. Portoghese and D M Ferguson, J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 381–391. (binding site model for fentanyl at the mu-opioid receptor).

- L. Došen-Mićović, J. Serb. Chem. Soc., 2004, 69, 843–854. (molecular modelling of fentanyl analogs)

- S. Vucković, M. Prostran, M. Ivanović, Lj. Dosen-Mićović, Z. Todorović, Z. Nesić, R. Stojanović, N. Divac and Z. Miković, Curr. Med. Chem., 2009, 16, 2468-2474. (structure-activity relationship of fentanyl analogues)

- A. V. George, J. J. Lu, M. V. Pisano and T. B. Erickson, Am. J. Emerg. Med., 2010, 28, 530-532 (carfentanil - ‘an ultra potent opioid’)

- A. Manglik , A. C. Kruse, T. S. Kobilka, F. S. Thian, J. M. Mathiesen, R. K. Sunahara , L. Pardo, W. I. Weis, B. K. Kobilka and S. Granier, Nature, 2012, 485, 321-326 (crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor)

- G. W. Pasternak and Y.-X. Pan, Pharmacol. Rev., 2013, 65, 1257–1317 (μ-Opioids and their receptors, review)

- W. Huang, et al., Nature, 2015, 524, 315- 321 (structural insights into μ-opioid receptor activation)

- O.Eriksson and G. Antoni, Mol. Imaging, 2015, 14, 476–483 ([11C] carfentanil binds preferentially to μ-opioid receptor subtype 1)

The opioid and fentanyl crisis

- J. Mounteney, I. Giraudon, G. Denissov and P. Griffiths, Int. J. Drug Policy, 2015, 26, 626–631 (rise of fentanyls in Europe)

- N. B. Tiscione and K. G. Shanks, Society of Forensic Toxicologists. ToxTalk, 2016, 40, 14–17 (carfentanil in driving under the influence of drugs cases)

- M. P. Prekupec, P. A. Mansky and M. H. Baumann, J. Addict. Med., 2017, 11, 256-265 (danger of highly potent opioids)

- K. McLaughlin, Science, 2017, 355, 1364-1366. (smuggling of carfentanil and other fentanyls, and their danger)

- S. N. Lucyk and L. S. Nelson, Ann. Emerg. Med., 2017, 69, 91-93. (‘an opioid epidemic within an opioid epidemic’)

- S. A. Schwartz, Explore, 2017, 13, 240-242 (‘America’s deadly opioid epidemic from which everyone but the users profits’)

- J. B. Cole, and L. S. Nelson, Am. J. Emerg. Med., 2017, 35, 1743–1745 (carfentanil and opioid poisoning)

- M. P. Prekupec, P. A. Mansky and M. H. Baumann, J. Addict Med., 2017, 11, 256-265 (new trends in synthetic opioid misuse)

- D. M. Swanson, L. S. Hair, S. R. Strauch Rivers, B. C. Smyth, S. C. Brogan, A. D. Ventoso, S. L. Vaccaro and J. M. Pearson, J. Anal. Toxicol., 2017, 41, 498–502 (fatalities involving carfentanil and furanyl fentanyl)

- N. D. Volkow and F. S. Collins, N. Engl. J. Med., 2017, 377, 391-394 (science and the opioid crisis)

- A. Cannaert, L. Ambach, P. Blanckaert and C. P. Stove, Front. Pharmacol., 2018, 9, 486 (suicide with carfentanil)

- N. B. Tiscione and I. Alford, J. Anal. Toxicol., 2018, 42, 476–484 (carfentanil impairs driving)

- I. Torjesen, BMJ, 2018, 361, k1564 (Fentanyl misuse in the UK: will we see a surge in deaths?)

- Carfentanil crisis on the streets.

- Carfentanil deaths in Hull

- Opioids: Why 'dangerous' drugs are still being used to treat pain (BBC News, 22 July 2018).

- Alternatives to opioids

- On America's trail of destruction BBC News, Oct 24th 2018

Fentanyl detection

- E. Sisco, J. Verkouteren, J. Staymates and J. Lawrence, Forensic Chem., 2017, 4, 108-115 (rapid detection of fentanyl derivatives)

- K. G. Shanks and G. S. Behonick, J. Anal. Toxicol., 2017, 41, 466–472 (detection of carfentanil in post-mortem specimens)

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.6139097]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.6139097]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Is that anything like fentanyl?

Is that anything like fentanyl?