![]()

Carminic Acid

Have you been eating insects your whole life?

![]()

Sydnee Craven

University of Adelaide, South Australia

![]()

Molecule of the Month May 2022

Also available: JSMol version.

![]()

|

Carminic AcidHave you been eating insects your whole life?

Sydnee Craven

Molecule of the Month May 2022

|

How on earth does this relate to insects?Have you ever eaten any of the following foods: Strawberry yoghurt, raspberry jam, canned cherries, strawberry liquorice, velvet cake or even sausages? Or have you ever used pink/red lipstick? If so, what do they all have in common? Well, they are all red! Often, this colouring is sourced from oval-shaped insects known as cochineal. Within an ingredients list, this colouring can be found under multiple names, including Carmine, Cochineal, Cochineal Extract, Natural Red 4, Crimson Lake, Carmine Lake, or E120. So, are these insects red?No, but it’s actually what’s inside them that matters. Cochineal naturally produce carminic acid which is a red pigment found within the insect’s blood. The acid naturally exists as a predatory deterrent but was also discovered to be a lustrous red pigment which is now used in the food, textile, and cosmetic industry ubiquitously. It is even used in mouthwash - so before you go rinsing your mouth out, you may just be rinsing it out with more bugs! |

The lustrous red pigment. [Photo: Stephhzz / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons]. |

|

| Structure of Carminic Acid with the five removable protons indicated. |

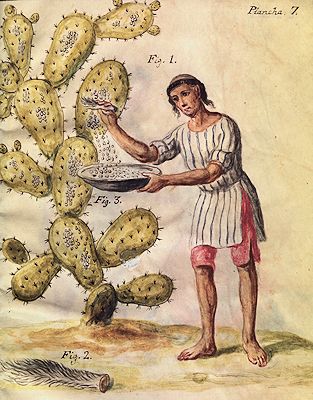

How is it obtained?Cochineal insects live and feed on the leaves of the prickly pear cactus. They can be easily mistaken for fungus as they exude a cottony white coating to protect themselves. Currently, Peru is the largest commercial producer of the insect, with plantations dedicated to growing cacti for the sole purpose of harvesting cochineal. The traditional and still widely used method begins by scraping cochineal off the cactus leaves. These insects are then dried and ground into a red powder mainly consisting of crude carminic acid.

|

The traditional and still widely used method of scraping cochineal from the leaves of prickly pears. [Photo: Alzate y Ramírez, José Antonio de / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons] |

Using ground-up dried insects to make pigments has been known since antiquity, but when the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire in the early 1500's, they encountered Aztec warriors dressed in a bright crimson colour that was brighter and more vivid than any dye they'd seen before. This was due to the cochineal insect (Dactylopius coccus) which was native to South America. The Spanish started shipping the dried insects back to Europe, and by the mid 1500's, tons of cochineal were being shipped to Europe for use in dyes.

After silver, cochineal became Spain's second most valuable export from the New World, and it contributed to Spain becoming one of the wealthiest and most powerful countries in Europe. The Spanish guarded the secret of its production carefully for centuries, and had a monopoly on the red pigment that was envied all over Europe.

Did the monopoly last?The red pigment was so sought-after that eventually other European countries found their own source of cochineal, and the pigment made its way around the world to be used in a multitude of applications. Such as?The British Army 'Redcoats' got their name from their woolen uniforms which were dyed bright red using cochineal. Actually it was only the officers' coats that were dyed with pure cochineal - the normal soldiers' coats were dyed with a diluted form of cochineal which made them appear a duller red. So-called 'Carmine lake pigment' made from cochineal was also used by artists such as Rembrandt and van Gogh in their paintings, and was highly valued for its vibrancy. Cochineal was also used for dying textiles until the emergence of synthetic aniline dyes, such as mauvine (see MOTM for January 1996), in the mid 1800s, which then took over the textile market. Nowadays it is most often found in foodstuffs and cosmetics as a 'natural' colourant. |

Reenactors in the uniform of the 33rd Regiment of Foot (Wellington's Redcoats), who fought in the Napoleonic Wars. [Photo: WyrdLight.com, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

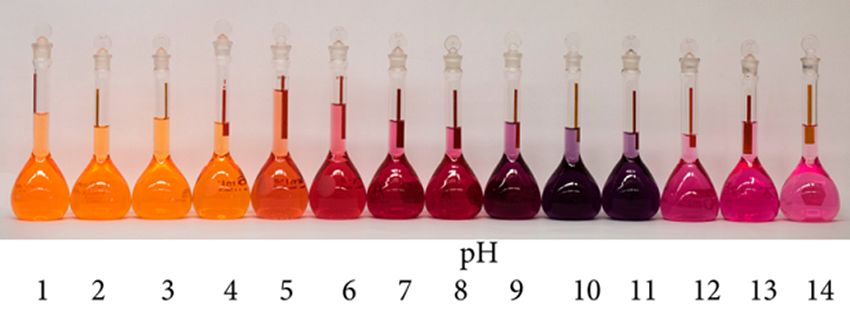

Carminic acid is a pH-dependent molecule. This means that depending on the pH there are several forms of the molecule possible based on whether it is deprotonated or protonated. Across the pH range, the molecule contains five removable protons. These include the carboxylic acid proton in position 1, in addition to four hydroxyl protons in positions 2, 3, 4, and 5 (see structure above). This can cause significant colour variations. For example, in acidic solutions, the molecule appears orange, whereas, in basic conditions, it appears violet. Such variations are not desirable, especially in commercial settings where consistency is key.

Carminic acid can take on a range of colours depending on pH.

[Image: Liu et al., J. Chem. Educ. 2017, 94, 216.]

Well, to lock in carminic acid’s colour it is usually complexed with aluminium and calcium to produce carmine; an intensely red and stable precipitate. Carmine consists of two carminic acid molecules bridged by an aluminium metal, in addition to surrounding calcium. Specifically, the carminic acid molecules behave as bidentate ligands, donating electrons to the metal to form a stable coordination complex. This chelation results in carmine being less prone to colour changes and ensures a consistent red colour between pH 4-10. This is in comparison to carminic acid which only maintains a persistent red colour between pH 4-7.

Carmine dye - proposed structure.

But it’s still a highly variable dye?Variation in the quality of cochineal is a serious issue leading to visible colour differences in the end product. Differences in climate, soil type, moisture, season, and geography all affect the quality and composition of the cochineal. Even differences in the methods of killing and drying the insects lead to variable colours. In fact, it has been shown that hastily harvested cochineal results in body parts, insect secretions, and plant matter being present. Although, modern operations attempt to reduce variability, for example, by carefully controlled heating methods to ensure uniform quality. I assume that makes it quite controversial?Yes. Back in 2012, Starbucks' customers (in particlar vegetarians and vegans) in the US were unhappy to learn that the red dye was being used in the Strawberries & Cream Frappuccino, the Strawberry Banana Smoothie, and the Red Velvet Whoopie Pie. This caused the ‘bug dye’ to attract headlines around the world, with Starbucks eventually dropping the dye opting for lycopene (see MOTM for January 2020), a red pigment in tomatoes instead. Is there anything else I should know?Overall, carmine is widely used in commercial products, tasteless, generally well-tolerated, and doesn’t have any specific health risks. Although the thought of the bug-derived colouring in our food can sound unappealing, it is probably better than some of the alternative synthetic dyes which may be carcinogenic and which are sourced from coal tar or petroleum. |

A newspaper article about the 'bug dye' controversy'. |

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.19657269]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.19657269]