![]()

Digitalis

A treatment for heart disease.

![]()

Paul May

University of Bristol

![]()

Molecule of the Month - September 1996

(Updated Aug 2016)

Also available: HTML version.

![]()

|

DigitalisA treatment for heart disease.

Paul May

Molecule of the Month - September 1996

|

|

|

Yes, it’s an example of a cardio-active or cardiotonic drug, in other words a steroid which has the ability to exert a specific and powerful action on the cardiac muscle in animals. The term digitalis is used for drug preparations that contain cardiac glycosides, in particular digoxin. This works by increasing the intensity of the heart muscle contractions but diminishing the rate, and has been used in the treatment of heart conditions ever since its discovery in 1775.

That’s a surprisingly long time ago for a modern drug?

That’s a surprisingly long time ago for a modern drug?That’s because the active ingredient is based upon an extract of the common foxglove, found commonly all over Europe.

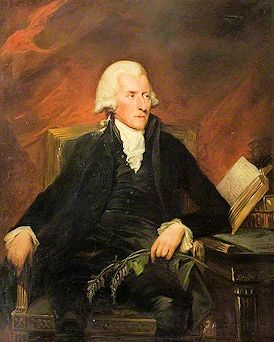

In the 18th century an English doctor called William Withering (1741-1799) (see image, right) was working as a physician in Staffordshire, England. As a hobby he became interested in plants and botany in general, and he became such an expert in the local flora that he published a huge textbook whose title begins ‘A botanical arrangement of all the vegetables growing in Great Britain...’ and continues for a further 24 lines! By the age of 46 he'd become the richest doctor outside of London, and bought Edgbaston Hall in Birmingham, which is now Edgbaston Golf Club.

There is a sort of urban legend that has grown up around this. The story goes that in 1775, one of his patients came to him with a very bad heart condition, but at that time there was no effective treatment for this so the odds didn’t look good for the patient’s survival. However, the patient - not discouraged by the inability of conventional medicine to treat his ailment - went instead to a local old woman (some reports say she was a gypsy), who gave him a secret herbal remedy. Astonishingly, the remedy seemed to work, and the patient got much better!

When Withering heard about this, he became quite excited and searched for the old woman throughout Shropshire. When he eventually found her, and after much bargaining, the gypsy finally told her secret – the herbal remedy was made from a concoction of over 20 different ingredients, one of which was an extract of the purple foxglove (photo, left). Withering was not surprised by this, as the potency of digitalis extract had been known since the dark ages, when it had been used as a poison for the mediaeval 'trial by ordeal', and also used as an external application to promote the healing of wounds. Digitalis has also been a remedy for dropsy, which was the old term for swelling of soft tissue in the legs and arms. Unknown to the physicians at the time, these swellings were often caused by poor blood circulation due to heart problems. Recently, researchers have questioned whether the 'Old Woman of Shropshire' actually existed, and that maybe Withering's vast knowledge of natural medical remedies was the real reason for him linking foxgloves and heart disease (although it doesn't make for such a romantic story).

When Withering heard about this, he became quite excited and searched for the old woman throughout Shropshire. When he eventually found her, and after much bargaining, the gypsy finally told her secret – the herbal remedy was made from a concoction of over 20 different ingredients, one of which was an extract of the purple foxglove (photo, left). Withering was not surprised by this, as the potency of digitalis extract had been known since the dark ages, when it had been used as a poison for the mediaeval 'trial by ordeal', and also used as an external application to promote the healing of wounds. Digitalis has also been a remedy for dropsy, which was the old term for swelling of soft tissue in the legs and arms. Unknown to the physicians at the time, these swellings were often caused by poor blood circulation due to heart problems. Recently, researchers have questioned whether the 'Old Woman of Shropshire' actually existed, and that maybe Withering's vast knowledge of natural medical remedies was the real reason for him linking foxgloves and heart disease (although it doesn't make for such a romantic story).

Well, over the next nine years Withering tried out various formulations of digitalis plant extracts on 160 patients with heart ailments. He found that if he used the dried, powdered leaf, without boiling them in liquid (which destroyed the active ingredients) he got amazingly successful results, and the painful angina symptoms of the patients went away. He introduced its use officially in 1785.

Digitalis purpurea plants contain a mixture of several cardiac-active molecules related to digitalis in amounts and proportions which vary with locality and with season. Before modern synthetic methods, therefore, digitalis preparations varied considerably in potency and quality. Because of this, and the fact that the therapeutic dose is so small (as low as 0.3 mg daily are all that is needed), it was very easy to exceed the safe dosage. Indeed, Withering recommended that the drug be diluted and administered repeatedly in small doses until a therapeutic effect became evident. This procedure was very effective in experienced hands, but was also very time-consuming.

Even today, drugs based on digitalis extract, such as Digitoxin and Digoxin, are some of the best known treatments to control the heart rate. Nowadays, preparations from digitalis leaves are made using modern recrystallisation methods and are carefully standardised by bio-assay.

Well, it’s actually several molecules. Hydrolysis of the digitalis extract produces many related molecules, all of which contain an α,β-unsaturated lactone ring (or cyclic ester) in addition to other structural similarities. Both the C14(β) hydroxyl group and the unsaturated lactone are essential to its activity as a drug. As well as digoxin (shown above), three other common ones are shown below.

|

|

|

Digoxygenin |

Digitoxygenin |

Gitoxygenin |

What happened to Withering?In 1799, Withering became very ill and it looked as though he was going to die. One of his friends, who was noted for his black sense of humour, wrote in a letter to a friend 'The flower of Physic is withering...', which is a very clever pun – if a bit tasteless. When Withering finally died, his friends carved a bunch of foxgloves on his memorial. AcknowledgementsThanks to Roy Sinclair for information about Withering and the controversy over the existence of the Old Woman of Shropshire. BibliographyGeneral

|

|

![]()