What's so special about linalool?

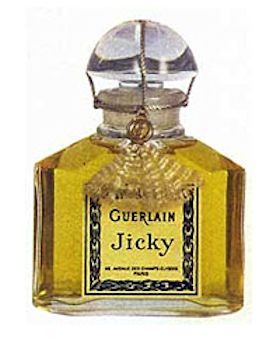

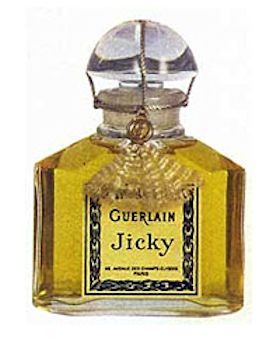

It is produced by a huge number of plants in most parts of the world, and has been an ingredient in perfumes for many years, starting with the classic Jicky (Guerlain, 1889) along with vanillin. The most famous lavender-based perfume is probably Jean Paul Gaultier’s Le Male (1995).

Lavender perfumes. Left: Jicky. Right: Le Male.

Why is lavender used in perfumes?

Why is lavender used in perfumes?

Lavender has a pleasing smell, thanks to the molecules it contains, like linalool. It is relatively easy to grow (think of the lavender fields of Provence, and also of Heacham in Norfolk, England) so lavender oil is much cheaper than rose oil or jasmine. Lavender is also used in aromatherapy. Research has suggested that it reduces stress, not just in humans but also in rats, though it seems that more tests are needed.

Linalool actually exists in two forms.

Why is that?

Because carbon atom 3 in the molecule is a stereogenic centre, as it has four different groups attached, so there are two stereoisomers.

|

|

(R)-(-)-linalool | (S)-(+)-linalool |

|

|

What is the difference between them?

They have identical properties like boiling point, density, refractive index and solubility. Chemically they have the same reactions, but they have different smells – not just to humans, insects like the Cabbage Moth can tell them apart.

What do they smell like?

(S)-(+)-linalool, from coriander oil and sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) has a smell described as sweet lavender with a touch of citrus; it is also found in tomato. (R)-(-)-linalool, found in the oils of rose, neroli and lavender, laurel and sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) has a more woody lavender smell. Mediterranean basil is used to make Pesto sauce alla Genovese with added ingredients like cheese, olive oil and walnuts. Its (R)-Linalool combines with methyl cinnamate, eucalyptol and estragole to create its odour.

|

|

Pesto Genovese | Clarkia breweri |

Linalool is produced by many plants, for example (S)-linalool is an important ingredient of the sweet scent emitted by flowers of Clarkia breweri (found only in California) to attract the moths that pollinate it. It is also emitted by many plants when they are damaged by herbivores, so it is probably involved in plant defence, maybe in summoning up predators. Thus when fall armyworm larvae damage rice plants, terpenoid volatiles, of which linalool is the most abundant, attract parasitic wasps.

Are the two forms found together?

Are the two forms found together?

Most natural materials contain (almost) exclusively one enantiomer, but laboratory synthesis generally gives a mixture. Genuine lavender oil is at least 85% (R) –enantiomer; likewise the (S)-isomer of linalool predominates (94-96%) in authentic sweet orange oil. So determination of enantiomeric composition can provide a test for any adulteration and of the authenticity of the oil.

What kind of plants make it?

Apart from the lavender plant (photo, right), it crops up in tea and coffee, whilst it is an important part of the aroma of hops (and beer). It is found in many other fruit, including guava, peach, plum, pineapple and passionfruit. Linalool is an important ingredient in orange juice.

How do plants make it?

Linalool is a monoterpenoid – made up structurally from two isoprene fragments and also containing a functional group.

Plants, though, don’t make it by joining isoprenes together. As so often, biosynthesis starts with acetyl coenzyme A, which undergoes a series of enzyme-controlled reactions to generate mevalonic acid; this in turn affords isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), whose more stable isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) is a source of a carbocation which reacts with an IPP forming geranyl pyrophosphate. These reactions are controlled by monoterpene synthase enzymes, and it is one of these, linalool synthase, that is responsible for the formation of linalool.

How can you make linalool in the lab?

A classic synthesis employed by Ruzicka and Fornasir used nucleophilic attack of the acetylide ion upon methyl heptenone to afford dehydrolinalool. Selective reduction of the alkyne linkage with sodium gave linalool.

In another approach due to Normant, vinyl magnesium bromide (or chloride) reacts with methylheptenone forming linalool on work-up.

Linalyl acetate is an ester of linalool that is also an important part of lavender. It may be formed by plants by the action of acetyl coenzyme A on linalool.

Because of its pleasant smell, it is sometimes used to adulterate poor quality lavender oil, to pass it off as a superior product which commands a much higher price.

Bibliography

General

- Chapman and Hall Combined Chemical Dictionary compound code numbers: - JXL03-D; JXL03-E (R)-form ; JXL03-F (S)-form

- G. Ohloff and E. Klein, Tetrahedron, 1962, 18, 37-42 (absolute configuration)

- H. Boelens, in E. Theimer (ed), Fragrance Chemistry: The Science of the Sense of Smell, New York, Academic Press, 1982, esp. pp 136-145.

- C. S. Sell, A Fragrant Introduction to Terpenoid Chemistry, Cambridge, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2003.

- E. Breitmaier, Terpenes: Flavors, Fragrances, Pharmaca, Pheromones, Weinheim, Wiley-VCH, 2006.

- J. S. Yuan, T. G. Köllner, G. Wiggins, J. Grant, N. Zhao, X. Zhuang, J. Degenhardt and F. Chen, Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2008, 3, 720-721.

- T. Yang, G. Stoopen, M. Thoen, G. Wiegers and M. A. Jongsma, Plant Biotechnol. J., doi: 10.1111/pbi.12080, 2013 (linalool and plant defence)

Synthesis

- L. Ruzicka and V. Fornasir, Helv. Chim. Acta, 1919, 2, 182-188 (Synthesis using sodium acetylide).

- H. Normant, Compt. Rend., 1955, 240, 631-633

- H. E. Ramsden, J. R. Leebrick, S. D. Rosenberg, E. H. Miller, J.J. Walburn, A.E. Balint and R. Cserr, J. Org. Chem., 1957, 22, 1602-1605. (Synth using Grignard)

Sources of linalool

- D. Wang, K. Ando, K. Morita, K. Kubota and A. Kobayashi, Biosci. Biotech. Biochem., 1994, 58, 2050-2053 (linalool in tea)

- G. Lermusieau, M. Bulens and S. Collin, J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3867-3874 (linalool in hops).

- E. Lewinsohn et al., Plant Physiol., 2001, 127, 1256-1265 (S-linalool in tomato).

- R. Bazemore, R. Rouseff and M. Naim, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2003, 51, 196–199 (orange juice).

- H. T. Fritsch and P. Schieberle, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2005, 53, 7544-7551 (Linalool in Bavarian beer).

- B. Bonnländer, R. Cappuccio, F. S. Liverani and P. Winterhalter, Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 637–641 (enantiomer analysis in coffee)

- K. Roth, Chemie in unserer Zeit, 2006, 40, 200 – 206. English translation at: - http://www.chemistryviews.org/details/ezine/1422625/Pesto__Mediterranean_Biochemistry.html. (linalool in pesto)

- M. Averbeck and P. Schieberle, Eur Food Res Technol., 2009, 229 611-622 (orange juice).

- F. Van Opstaele, G. De Rouck, J. De Clippeleer, G. Aerts and L. De Cooman, J. Inst. Brewing, 2010, 116, 445 -458 (linalool in beer)

- H.-G. Schmarr and K.-H. Engel, Eur. Food Res. Technol., 2012, 235, 827-834 (cocoa)

- G. Amadei and B. M. Ross, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom., 2012, 26, 219-225 (linaolool in basil)

Lavender

- S. Hanneguelle, J.-N. Thibault, N. Naulet and G. J. Martin, J. Agric. Food Chem., 1992, 40, 81–87 (Authentication of lavender oil)

- M. Guitteny, Lavender, Monaco, Société Agar, 1998.

- C. Meunier, Lavandes et lavandins, Edisud, 3rd ed, 2000.

- G. Ohloff, W. Pickenhagen and P. Kraft. Scent and Chemistry. The Molecular World of Odors, Verlag Helvetica Chimica Acta, Zurich, 2011, esp. pp 242 – 247 (Lavender in perfume)

Lavender and stress.

- M. Moss, J. Cook, K. Wesnes and P. Duckett, Int. J. Neurosci., 2003, 113, 15-38; L. Neale, L. Moss and M. Moss, Int. J. Clinical Aromatherapy, 2008, 5, 3-8. (soothing lavender)

- A. Nakamura, S. Fujiwara, I. Matsumoto and K. Abe, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2009, 57, 5480-5485 (stress reduction in rats by (R)-(−)-Linalool)

- P. H. Koulivand, M. K. Ghadiri and A. Gorji, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013, Article ID 681304 (review : lavender and the nervous system)

Enantiomers

- Y. Sugawara, C. Hara, T. Aoki, N. Sugimoto and T. Masujima, Chem. Senses, 2000, 25, 77 – 84. (enantiomer smell discrimination in humans)

- M. L. R. del Castillo, M. M. Caja and M. Herraiz, J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1284-1288 (linalool enantiomers in orange drinks).

- W. A. König and D. H. Hochmuth, J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2004, 42, 423-439.

- A. Mosandl, J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2004, 42, 440-449 (authenticity of lavender)

- S. Ulland, E. Ian, A.-K. Borg-Karlson and H. Mustaparta, Chem. Senses., 2006, 31, 325-334. (Cabbage Moth discriminates between enantiomers of linalool)

- R. Bentley, Chem. Rev., 2006, 106, 4099-4112 (enantiomer discrimination)

Biosynthesis

- E. Pichersky, E. Lewinsohn and R. Croteau, Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 1995, 316, 803 – 807 (S-linalool synthase in Clarkia breweri)

- R. A. Raguso and E. Pichersky, Plant Species Biology, 1999, 14, 95-120 (Linalool biosynthesis in flowering plants)

- W. Schwab, R. Davidovich-Rikanati and E. Lewinsohn, The Plant Journal, 2008, 54, 712–732 (Biosynthesis of plant-derived flavour compounds)

- A. Zaks, R. Davidovich-Rikanati, E. Bar, M. Inbar and E. Lewinsohn, Isr. J. Plant Sci., 2008, 56, 233–244 (Biosynthesis of linalyl acetate in lemon mint)

Back to Molecule of the Month page.

Back to Molecule of the Month page.

Why is lavender used in perfumes?

Why is lavender used in perfumes?

Are the two forms found together?

Are the two forms found together?

![]()

![]()