|

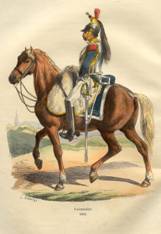

Brilliant Tactician and Strategist? The phenomena Napoleon: an unbelievable understanding of terrain, mobility of units, concentration of power and support of the fighting moral! Bernard Montgomery, Viscount of Alamein A matter-of-fact investigation has started, asking whether and how much Napoleon really was a brilliant strategist. He is often simply presented as such - thereby freeing all his adversaries, who still enjoy completely undeserved sympathy, of being accused of human incompetence. The fact is that Napoleon took over a well developed army system, based on the efforts of Carnot. Very little of the equipment and tactics had changed. Only in the artillery, the branch of service where Napoleon had started - his original request had been a transfer to the navy, but due to his extremely impressive achievements in mathematics this wish was not granted and he was ordered to enter the artillery -, drastic and tactically important changes were made. These included the system of independent regiments and the usage of artillery as independent troops - thereby moving away from the pure battalion formation towards larger and much larger units - as well as the development of highly mobile horse artillery. What he carried with him in any case, as a well trained officer with a keen interest, was a long lasting study of the military sciences, which in that time meant extensively studying military history. He seems to have been especially a student of Frederick of Prussia, using his tactics and refining them, adding the possibilities that larger armies bring. In addition, he had an outstanding eye for terrain - also not new, but still special. And a gift, to be able to motivate his troops, even though Napoleon's speeches should not be overrated. A soldier going to war would rather do this under command of a proven competent commander. All that nonsense about troops loving an emperor or king, or a "fatherland", must be seen relatively, except perhaps when dealing with a hysterical fanatic who will go for any "leader's" plan - even today. Even in Tyrol the problems with Bavaria were about taxes and jurisdiction, not about Johann or Franz von Habsburg, and only very little about matters of the church. In Spain, the things that mattered to the clergy (!) and nobility of the Junta were property and benefice, not "freedom", national independence, or the much loved Bourbons. Furthermore, the factor the English played in Spain, the Moorish armies and Wellington, isn't given the attention it deserves. The Spanish Insurrection would not have come very far without British military aid - in contrast to the irresponsible uprising started by the Habsburgs in Tyrol, which in the long run proved of little help -, which entered by way of Spain's extensive coasts. Also, the fast march based on the troops living of the land wasn't actually "invented" by Napoleon, but was already used in the first campaigns of the revolutionary armies and was more an emergency situation which they turned into a strength. Napoleon himself understood this all too well. He later said that the potato - introduced only decades before as a crop - was the crucial basis of his marching achievements and victories; potatoes could not be found in the sparsely populated and generally poor Russian territories and even before the invasion of 1812 the supplies of at least 11 to 17 battalions could not be filled. Other things, as tactically important as the fast march, were also taken over from the revolutionary times. These included the attack in massed columns, the close deployment of skirmishers ahead of a main body, and the combination of infantry in line formation with attack columns. What distinguishes Napoleon is his masterful control of these instrument, his outstanding preparation of his campaigns, which permitted him to hit hard, even if the map showed something other than expected. Again and again he succeeded in gathering his inferior number of troops from the whole campaign area at a single point and, on the day of battle, building up an overpowering attack over a decisive flank or right at an enemy's weak center. In principle this was a strategy that fitted Frederick's "asymmetrical battle formation". Napoleon would often combine this with a flank attack, depending on the terrain at one or the other side of the enemy. For this large formations were often employed. Comparatively new was that when he used an asymmetrical battle formation and flank attack, not only did he create a numerical superiority but at times also successfully used a break-through in the center as a tactical possibility. But the fact is also that in reality this procedure always failed when the conditions weren't there, as was the case in Russia and in Spain. With his assessment of terrain during moments of unexpected difficulties it wasn't so far away. When he realized this later himself, for instance after Russia, his defense was that he had to plan a possible second campaign, so his opponents had an advantage, while he had to maneuver himself into unusual strategic and tactical situations and could then be threatened by his own "weapons", concentration of a large force in a small area. Something made impossible for Kutusow at Austerlitz by the featherbrained and vain tsar. Radetzky then succeeded at Leipzig thanks to the "diplomatic" abilities of his commander Scharzenberg towards emperors and kings: being allowed to wait for the concentration of a decisive supremacy of numbers. What also distinguishes him was his extremely detailed knowledge of marching routes and his brilliant estimates of achievable marching distances by his troops, which often gave him the crucial head start of two or three days before combat. For instance, in the situation of the Austrians breaking the treaty and attacking in 1805, it could have turned out the same way as at Leipzig if the Russians had been there earlier than Napoleon. But the Austrians were too slow, the Russian invasion was spotted in time. Also, the role of his commanding officers should not be underestimated. When they failed, as Grouchy did at Waterloo, even Napoleon couldn't do anything about it. The role of the commanders was critical at a time when troop formations were becoming larger and larger, while communications in combat was still very tricky and plagued by misunderstandings. And here is also the place to acknowledge his physical capabilities, his genuine "flair", and his consideration of the common man as well. Even during the time of the empire - and this was deeply appreciated by al his men - he addressed his troops with the very personal "tu" and for a long time it was actually possible to rise through the ranks up to the highest positions, simply by effort and courage, to find a "marshal's staff in your knapsack", so to speak. Decorations bloodily fought against during the Revolution are also introduced again, right up to Legion of Honour and titles formerly assigned by the king, like "marshal", to the most deserving men. Napoleon shows that as a professional soldier he also thinks in the classic and (perhaps not unlogical) classes when he gets rid of the new system of voting for officers. This is one of his more regrettable decisions, and one should consider whether this addition element of democracy should not be reinstituted. Not in the sense of abolishing the strict qualifications for being an officer, but that before someone can pursue a career as an officer, he must at least once be subjected to a vote by his subordinates. Many very problematic characters and subsequent problems of our present armies could be prevented that way. Concerning Napoleon, he indeed neglected appointing new officers in the highest ranks during his last reigning years - which in the end harmed him very much, because the failure (perhaps even betrayal) of his highest officers, like Grouchy, was probably the last straw for his final defeat. In retrospect, he said himself - once again, too late - that in the period before Waterloo he should have entrusted the important commands to new, energetic officers instead of the old marshals. Which stands in full contrast with the outrageous comment made by one of his marshals: "It's all his own fault, really. He took the begging bag off our shoulders much too early!" From Marmont, to Ney, to Murat, after 1812 they fought for nothing more than the preservation of their income and lordships. Napoleon himself always kept his loyalty to his old brothers in arms - too long, regarding the preservation of his empire. And he never committed a single act of revenge after his return from Elba. Two further, very important tactical Napoleon "improvements" must be explained in a more detailed way: The first one was broadening the structure of the Elite Corps which existed already, but not to this extent, they hadn't been formed and molded in a broad manner and this was one of Napoleon's intentions. Frowned on during the revolution - there was a recognition of Elite troops in the Era of the Nobel, but this was not to be extended during the ruling of Napoleon - he quickly expanded them so that in every layer of troops elite forces would emerge. This way the troop reserves, which originated from the Consular Guards with about 9.754 men in 1804, was raised at the high point of the "Grand Army" at an estimated 56.000 men in 1812. But to this fact there was the contradiction that the systematical integration of high volumes of units into "older regiments" would have to be done at a slow pace to hold the integrity of the regiments so that their expansion wouldn't become their weakness. To the concern of the Guards, they enlisted new troops by searching among the new "elite officers", from these they picked the most suitable ones. This had to be done because these troops would be exposed directly to combat and had to face the psychological and mental hardness of this - wars may have been more colourful then, but they were just as horrible. The second very important improvement was the realization and accentuation of the cuirassiers as heavy armored cavalry. The heavy cavalry had discarded their armor piece by piece during the 30 Years War. Even the Imperial-Austrian Cavalier wore only breast plates in 1767 and the Prussians had abolished this kind of armor since 1790, England barely had any cuirassiers tradition and the USA had no armored cavalry whatsoever. As consul, Napoleon reinstated the use of armor in big numbers back in the year 1802. Armor was to be worn on the breast and the back and was fabricated from cold rolled sheet steel, this was bulletproof because of the thickness (approximately 10 kilos or 20 pounds heavy) and curves in the steel of up to 80 degrees. For Napoleon it wasn't about the actual protection of the men, but rather Napoleon's thoughts and awareness that the units who would wear this would think that it would be extremely more difficult to get injured or worse, get killed, so in this way, Napoleon was fooling his men by giving them this idea. This contributed of course that those men were much more motivated and had an increased sense of security. This feeling was invigorated by the bullet marks on the chest and back plates which would be shown to the troops and made them feel more secure and would increase there willingness to take bigger risks in battle. Embroidered metal pieces into the epaulettes would improve the protection from bullets as well. The dragoons had, during the Napoleon era, evolved from their origin of "mounted infantry" into unarmored heavy cavalry. This way they were given a special function in the conquest of England, as they were to be entering England in the first wave of troops and had the capability of fighting on foot because they were equipped to do so. The second step would be to capture horses when the opportunity presented itself and becoming a cavalry unit once again. On the other hand, it is very surprising that although Napoleon was a very innovating person, he lacked interest in improving the weapons with which his troops were equipped. The infantry still used the musket model from 1777, which was very heavy and difficult to handle compared to it's counterparts. Admittedly, a technical commission was founded in 1800 by Napoleon, which was instructed to research the next generation of the musket. During this time Napoleon was given an example of an early model of a breech-loader. Whether this design could have been mass produced and would have been of any military use is very difficult, perhaps even impossible, to say, fact is that this design was rejected by Napoleon. Incidentally, it was much like the Austrian air gun from around 1790, which had a pneumatic based repetitive breech-loader that gave enormous advantages, like multiple shots, smoke-free, every advantage a breech-loader had, etc... As far as we know, the model in the Historical Museum of Vienna let's us see that this kind of weapon was primarily used by sharpshooters although it had a complex pneumatic-mechanical loading system. But this technically superior design too was not to be pursued, supposedly because at this time period it was not seen as "honourable" to use this kind of weapon! A similar phenomenon was the renouncement of the bayonet by the soldiers of the Ottoman Empire, especially by the Janissary, during the Napoleon era. They preferred to get stabbed by one then to use the weapon of the "dishounorable". In any case, one thing is clear, however unsensational it may be: the assurance of a French public finance system and the military draft, enforced by the "gendarmerie", in the most densely populated nation of Europe, as well as the excellently organized cooperation of fighting forces in division- and corps strength certainly had more influence on Napoleon's military achievements than exotic weapons technology! by Martin Walter, exclusive for Cossacks2-net.de |