Chapter 2

Growth and Characterisation of the Diamond Films

2.0 Outline

·

This

chapter describes the diamond growth method used in this study and explains why

it was chosen.

·

The

main components of the diamond growth apparatus are described.

·

The

benefits of four different types of electrical contact are compared.

·

Scanning

electron microscopy, optical microscopy and Raman spectroscopy were used to

characterise the films and the results are presented here.

2.1 The Choice of Growth

Technique

Hot filament chemical vapour

deposition (HFCVD) was used to grow diamond films for these studies. HFCVD

diamond was first produced in 1952. 61,62 The technique is now

established and has been well described in a number of review articles. 11,17,18

Extensive work has previously been performed on similar HFCVD set-ups at the

University of Bristol. 63-65

The chemical vapour

deposition (CVD) process had a combination of properties that made it the

method of choice for fabricating the diamond films in this study:

·

The

use of gaseous reagents was easily controlled and allowed the composition of

the reaction mixtures to be varied.

·

The

technique produces continuous films which, if grown on planar substrates, were

macroscopically flat. These films were ideal for use as planar electrodes. The

technique could also be extended to coat metal wires with diamond, 66 which could be used in a range of

alternative electrode geometries. 67

·

Diamond

films were produced which covered a surface area of several square centimetres.

While certain other techniques could coat significantly larger areas, much work

on the electrochemistry of diamond had previously studied smaller single

crystal diamonds and homoepitaxial layers grown onto single crystals. The

larger surface area available with CVD diamond allowed for a range of

electrodes to be fabricated that were ideal for laboratory experiments.

HFCVD was used in preference

to more sophisticated forms of CVD for a variety of reasons:

·

The

apparatus was sufficiently simple to allow thorough cleaning of the inside of

the reaction chamber. This was necessary to remove boron contamination.

·

The

relative simplicity of the design allowed for modifications to the chamber to

be introduced as required.

·

The

components necessary to assemble a HFCVD chamber are relatively inexpensive.

·

The

HFCVD technique has been studied extensively and there is a reasonable

understanding of the processes involved. The growth apparatus used in this

study was a modified version of a well characterised HFCVD chamber and this

significantly reduced the work necessary to characterise and optimise the

growth conditions.

The use of HFCVD applied a

number of restrictions on work that could be performed:

·

HFCVD

does not give the high rates of growth available from certain other techniques,

such as plasma torches, 19,68 and so thick films could not be grown.

If sufficiently thick diamond films had been grown then the silicon substrate

could have been etched away in a bath of hydrofluoric acid (HF) and nitric acid

(HNO3). 69 This

would have left a free-standing diamond film which can be used in a range of

applications.

·

The

use of hot-filament CVD prevented the use of any oxygen containing gas species.

The presence of species such as oxygen (O2), carbon monoxide (CO),

carbon dioxide (CO2), trimethylborate (TMB, B(OCH3)3)

or water (H2O) would have caused the rapid burn out of the tantalum

(Ta) filaments.

·

Metallic

contamination of the diamond films from the filament was a potential problem.

The possibility of surface or bulk tantalum (Ta) affecting the electrochemical

or electrical properties had to be considered. 70,71 Any possible

effect of tantalum could be reduced if the diamond films were treated in acids

before use. Refluxing in hot nitric acid could be used to remove any graphitic

(sp2) content in the surface layer of the films and a short (ten

second) dip in warm chromic acid (H2Cr2O7) † could be used to oxidise the surface of

the films.

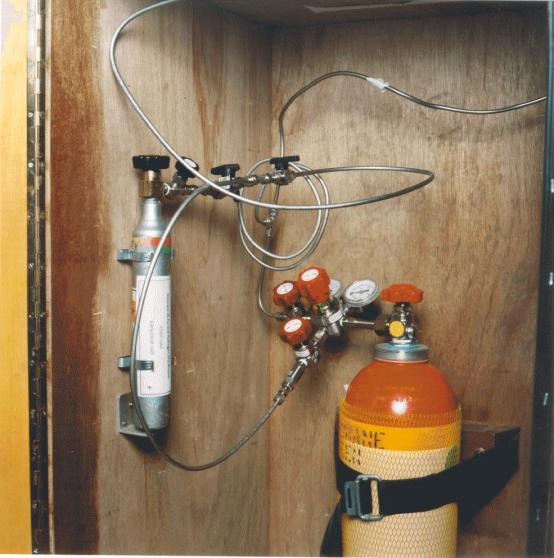

Figure 2.1 - A schematic diagram of the gas lines which fed the diamond CVD chamber

2.2 The Reaction Gases

Figure 2.1 shows a schematic

diagram of the experimental set-up of the gas lines which fed the reaction

chamber.

Hydrogen (H2),

methane (CH4) and diborane (B2H6) gases (BOC

Speciality Gases) were used in the growth process. See section 2.10 for details

of the reaction conditions.

Laboratory standard “high

purity hydrogen” and methane were used. The purities of the hydrogen and

methane were 99.995% (“N4.5”) and 99.5% (“N2.5”) respectively.

Diborane was chosen as the

boron source because it held advantages over most other sources. Table 2.1

summarises these advantages and disadvantages of commonly used sources.

|

Boron Source |

Formula |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

References |

|

diborane |

B2H6 |

· simple

molecular chemistry · gas source provides excellent controllability and variability of concentrations · availability† |

· highly toxic · highly explosive · highly reactive |

72 - 75 |

|

trimethyborate (TMB) |

B(OCH3)3 |

· non-toxic |

· liquid source requires dilution in acetone (CH3)2CO or methanol CH3OH |

78 - 84 |

|

boron (rod or powder) |

B |

· solid added directly to chamber - easy to store |

· lack of controllability and variability of concentration |

67, 85, 86 |

|

boron trioxide |

B2O3 |

· readily available |

· solid source requires dissolution in acetone (CH3)2CO or methanol CH3OH‡ |

87 - 91 |

|

ex-situ ion implantation |

B+ |

· can dope any diamond sample · good controllability · achieve low doping levels |

· non-uniform doping profile · damage to diamond sample due to high energy bombardment |

93 |

Table 2.1

A summary of the advantages

and disadvantages of various boron sources

The diborane was a special

order gas which was supplied as a 4.75% premix of diborane in hydrogen.

Diborane is a highly explosive, toxic and reactive gas. Great care was taken to

ensure that all gas lines were leak tested before use. The gas cylinder, the

dilution cylinder and the associated piping were housed in a specially designed

fume cupboard to provide some secondary protection in the event of an accident.

The reactivity of diborane made it necessary to avoid the use of many materials

including brass and nitrile rubber.

The source gases were stored

in gas cylinders with nominal pressures up to 200 bar at 15 °C.

Regulators reduced the cylinder pressures to the level of one to two bar above

atmospheric pressure. Mass flow controllers then set the flow rates into a gas

manifold where the gases mixed before they flowed along a common gas line into

the reaction chamber.

The regulator on the

diborane gas cylinder was a stainless steel single stage design which could be

pumped down to vacuum and contained a purge line. This also allowed the

dilution procedure to be performed (see section 2.4). The hydrogen and methane

gas cylinders used standard single stage brass regulators.

Low levels of impurities in

the hydrogen gas could be significant because of the relative flow rates of the

source gases. A typical gas mixture may use as many as seven orders of

magnitude more hydrogen than diborane. Therefore an impurity species in the

hydrogen with a concentration of only one hundred thousandth of one percent

(0.00001%) would have a concentration in the mixture of gases comparable to

that of the diborane present. Fortunately, nitrogen (N2), the main

impurity present, did not effect the growth process or the electrical

characteristics of the diamond films. Nitrogen is not incorporated into diamond

during growth as rapidly as boron 94 and it tends to occupy

electrically inactive sites. 95-97 The effects of nitrogen on the

growth rate and surface morphology of the diamond also require higher

concentrations than present in the reaction mixture. 98-99

2.3 The Mass Flow

Controllers

A bank of three mass flow

controllers (MFCs) was used to set the flow rates of the gases. Each MFC

controlled the flow of gas through a gas line and into a manifold where the

gases were mixed. The MFCs were manufactured by Tylan General and their

specifications are detailed in Table 2.2.

The MFCs were controlled

electronically and could be adjusted to give a wide range of flow rates. They

performed less well if the rate of flow was reduced below five percent of the

maximum flow rate and so alternative methods was needed to obtain low flow

rates. For this reason, the diborane MFC was replaced with a lower capacity

model when boron doping levels below 3000 p.p.m. were to be achieved.

The MFCs could be set to

115% of their nominal maximum flow rate to enable rapid pumping down of the

system. However, this was not sufficient to allow the diborane line to be

pumped down in a reasonable time and so a bypass valve was fitted beside the

MFC. The diborane MFCs used viton seals and were compatible with the gas.

|

MFC number |

Gas |

Calibration |

Range (s.c.c.m.) |

Conversion |

|

|||||

|

1 |

Hydrogen (H2) |

Hydrogen |

0 - 200 |

1 |

|

|||||

|

2 |

Methane (CH4) |

Nitrogen |

0.0 - 10.0 |

0.72 |

|

|||||

|

3 |

Diborane (B2H6) |

Hydrogen |

0.0 - 10.0 |

1 |

|

|||||

|

4 |

not used |

|

|

|

|||||

Table 2.2 - Specifications

of the Mass Flow Controllers

A fourth MFC was available

to allow more gases to be added to the reaction mixture. This facility was not

used in this study. However, it has been proposed that adding hydrogen sulphide

(H2S) or ammonia (NH4) would enable co-doping of the

diamond film with sulphur (S) or nitrogen (N) respectively.

The mixing manifold had a

second output to allow the MFCs to be used to supply other experiments with

hydrogen or methane when the CVD chamber was not running. In particular, the

hydrogen line was used to supply a prototype liquid CVD reactor.

2.4 Dilution of the Diborane

Gas

The diborane gas was

supplied pre-mixed with hydrogen. The nominal concentration was five percent

diborane in hydrogen. This proved far too concentrated for the deposition of

low doped diamond films and so a dilution system was constructed which allowed

the premix to be further diluted with hydrogen. This process could be performed

a number of times to allow the levels of diborane in the reaction mixture to be

reduced by several orders of magnitude. A lecture bottle with a capacity of 0.4

litres was used as a mixing vessel. Once the diborane was diluted, the lecture

bottle acted as a reservoir which could supply gas for approximately twenty

hours at a typical flow rate equivalent to 4 × 10-5 s.c.c.m.

of pure diborane. A photograph of the dilution assembly is shown in figure 2.2.

Figure

2.2 -A photograph of the diborane dilution assembly

The dilution method was a

highly effective technique for obtaining low concentrations of diborane but it

added significantly to the error in the measurement. The pressures used in the

dilution procedure were read from the pressure gauge on the diborane regulator.

This was not sufficiently sensitive to give a highly precise reading and so the

random errors were significant. The calculation below shows the effect of a

triple dilution on the error in the measurement of diborane concentration. The

physical displacement of the gauge from the lecture bottle also gave rise to

the possibility of a systematic error.

The calculation below shows

the random error for a triple diborane dilution and using a formula given in

reference 100. The errors used for the readings are half a scale division.

Typical values for a triple diborane dilution:

molar fraction of diborane in premix, R = (0.0475 ± 0.00005)

pressure of first fill of diborane mixture, pD1

= (0.500 ± 0.125) bar

pressure of first fill of hydrogen dilutant, pH1

= (2.6 ± 0.1) bar

pressure of second fill of diborane mixture, pD2

= (0.500 ± 0.125) bar

pressure of second fill of hydrogen dilutant, pH2

= (2.6 ± 0.1) bar

pressure of third fill of diborane mixture, pD3

= (0.500 ± 0.125) bar

pressure of third fill of hydrogen dilutant, pH3

= (2.6 ± 0.1) bar

molar fraction of

fully diluted diborane = r

\ molar fraction of fully diluted diborane, r = 0.0034 ± 0.0006

The random error in the

measurement of the gas phase composition can be up to nineteen percent.

2.5 The Deposition Chamber

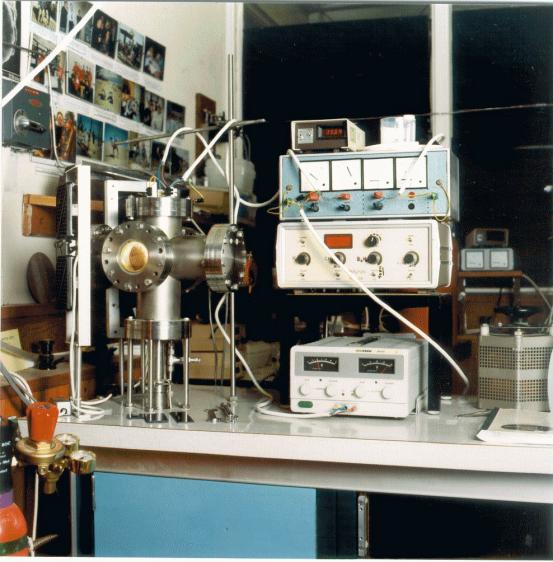

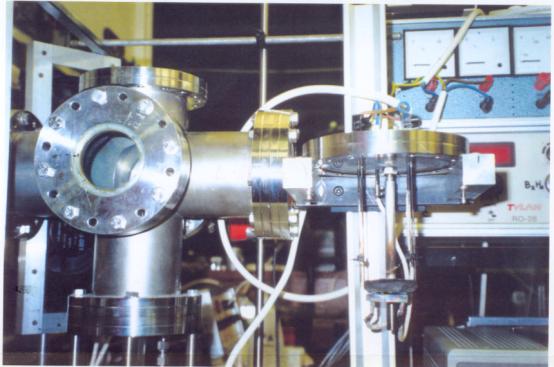

A photograph of the

deposition chamber is shown in figure 2.3.

Figure

2.3 -A photograph of the deposition chamber

The deposition chamber

consisted of a single-walled stainless steel six-way cross with welded joints

and bolted flanges.

The top flange incorporated

three pairs of electrical contacts made from tungsten (W) rods. Glass coatings

were used to electrically insulate the rods as they fed through the flange.

Vacuum seals were made with epoxy resin and silicone rubber. One pair of

contacts was used to supply power to the substrate heater and the other two

supplied power to the filaments. The deposition chamber was electrically

earthed by a cable attached to the top flange. The casing of the rotary pump

provided a second route to ground.

The front flange housed a

glass window which provided a viewing port to allow for visual inspection of

the reaction. The window also allowed for measurement of the temperature of the

hot filament using an optical pyrometer.

Three gas lines fed into the

reaction chamber via the rear flange: the reaction gas inlet leading from the

mixing manifold; a connection to a capacitance diaphragm pressure gauge

(Baratron) which was used to measure the pressure in the chamber during diamond

growth runs; and an air vent valve which allowed the chamber to be brought up

to atmospheric pressure before it was opened.

The bottom flange led to a

two-stage rotary pump via two stainless steel gas lines. A large bore line,

with an internal diameter (int. Æ) of approximately

20 mm, allowed the vacuum system to be pumped down rapidly. A narrow bore

line, int. Æ 3 mm, fitted with a needle

valve allowed for greater control of pressure required for diamond deposition.

The openings to both these lines were protected from debris by a copper (Cu)

gauze. The exhaust line from the rotary pump was safely routed to an outlet on

the roof of the building.

The flange on the left-hand

side of the chamber was blank while the right-hand one incorporated a spare

pair of electrical feed-throughs.

The top flange could be

readily removed for access to the chamber. The filament holders and substrate

heater assembly were attached to the underside of this flange, to allow the new

filaments to be fitted and the substrates to be loaded before the assembly was

loaded into the deposition chamber.

The other flanges could be

removed to allow for thorough cleaning of the system. This was required

whenever the level of boron contamination became too high to maintain

reproducible levels of doping in the diamond films. In practice, this procedure

was performed when the required boron doping level in the diamond films was

reduced significantly.

During operation, the

deposition chamber was air cooled by four fans.

2.6 The Substrate Heater

A substrate heater was made

from a coil of nichrome wire [nickel-chromium (Ni‑Cr) 24 SWG, standard

wire gauge]. The wire was threaded through insulating ceramic beads and then

coiled. The coil of wire was then encased in fire cement and gently heated to

allow the cement to set. It was important to drive off any water that could be

released into the chamber in order to prevent oxidation of the hot filaments. A

molybdenum (Mo) plate was placed onto the top of the cement block to provide a

flat surface on which the substrates could be placed. Molybdenum was chosen

because it has a high melting point, it is inert under the reaction conditions

and is effective in evenly spreading the heat to the base of the substrates.

The substrate heaters were

operated by passing a current of 4 A through the nichrome wire. A potential of

15 to 20 V was required to achieve this current depending on the length of wire

used in the construction of the heater. From previous studies on similar

systems, it is estimated that the hot filaments reached 2400 °C and provided

additional radiative heating which raised the substrate temperature to 900 °C. 64

The maximum operating temperature of the substrate heater was limited by the

breakdown of the fire cement at approximately 1000°C which would cause water

vapour to be released into the chamber and lead to burn out of the filaments.

The substrate heaters had an

operational lifetime in the order of eight hundred hours, after which the

resistance wires would become too brittle and break. This allowed for

approximately ninety growth runs during the life of the heater. The periodic

replacement of the heater was also important to reduce residual boron levels in

the chamber as the heating block could not be cleaned and the fire cement was

believed to be a significant source of contamination due to its porous nature.

Electrical connections

between the heating block and the tungsten feed-throughs were made with standard

copper flex insulated by ceramic beads.

An Iso-tech DC power supply

was used for the substrate heater and this was protected from overheating by an

external fan behind the heat exchanger at the rear of the unit.

2.7 The Filaments

The CVD reactor used

tantalum (Ta) filaments which were prepared by coiling a length of wire around

a 4 mm rod. The shaft of a screwdriver was routinely used for this purpose. The

wire used had a diameter of 0.25 mm. Previous work by the group had used

six-turns of wire which spanned approximately one centimetre. The chamber used

for this study was designed for larger scale deposition. It was found that ten

turns of wire spanning 2 cm was the optimum scale for the system as longer

filaments tended to sag during operation which resulted in poor diamond growth.

Figure 2.4

- A photograph of the deposition chamber showing the

internal

assembly after a deposition run - the heating stage and

a

drooping tantalum filament are visible

Previous studies had used

single filament set-ups. The chamber used for this experiment was a double

filament arrangement. This allowed for either a larger deposition area to be

covered or for two or more substrates to be coated simultaneously. The two

filaments were connected in series with the connection being made outside the

chamber. The apparatus could be readily reconfigured to allow single filament

operation using either the front or the rear filament. As well as allowing for

planned runs with single filaments, runs in which one of the two filaments

failed could be continued after a quick rewiring of the connections.

The filaments were attached

to tungsten (W) rods by stainless steel clamps, and the power supply was

provided by a Variac variable resistor with an external voltmeter and ammeter.

The current was maintained at 6.75 A throughout the diamond deposition as this

provided an optimum filament temperature of approximately 2400 °C. 64

The filaments could not be

operated at very low pressures as the evaporation of tantalum would be too

great. Under normal operating conditions, the methane in the gas mixture caused

carburization of the filaments as the malleable silver-coloured tantalum

reacted to form brittle gold-coloured tantalum carbide. As the filament reacts,

the resistance changes and so the potential had to be varied from 20 to 30 V to

maintain a current of 6.75 A. The filaments were replaced after each growth

run.

The tantalum wire (Aldrich)

used had a purity of greater than 99.9%, the levels of impurity are listed in

table 2.3.

|

element |

concentration (p.p.m.) |

|

Aluminium, Al |

120 |

|

Copper, Cu |

85 |

|

Tin, Sn |

80 |

|

Nickel, Ni |

35 |

|

Chromium, Cr |

20 |

|

Vanadium, V |

15 |

|

Magnesium, Mg |

1 |

Table 2.3 - Trace elements

in the tantalum wire

Values taken from Supplier’s

Certificate of Analysis

2.8 The Substrates

Silicon (Si) was used as a

substrate in all the films studied for the work described in this thesis,

although boron doped diamond films were also grown on tungsten (W) substrates

using the same reaction conditions.

The surface-area of the

growth side of the silicon substrates varied from 1 cm2 (1 cm ´ 1 cm) to 4 cm2 (2 cm ´ 2 cm). Typically two 2 cm2 (2 cm ´ 1 cm) substrates would be placed

next to each other on the heating stage to allow two diamond films to be

fabricated per growth run. This allowed for better control experiments and

increased the production rate of the electrodes. The substrates were obtained

by cutting or breaking pieces of silicon from silicon wafers reclaimed from the

microchip fabrication industry. The thickness of these wafers varied from ½ mm

to 3 mm. The surface of the substrate requires pre-treatment to enhance

nucleation of diamond growth sites at the start of growth process. The

pre-treatment used was manual abrasion of the surface by rubbing with 2-3

μm diamond powder followed by cleaning in 2-propanol (IPA). A two stage

cleaning process was employed. An initial cleaning with IPA soaked cotton buds

was followed by a 15 minute ultrasonic bath in IPA.

If the diamond film was to

be doped throughout and electrical connections made through the silicon

substrate then the substrate would be dipped in hydrofluoric acid (HF) and

rinsed in 18.2 MW cm ultrapure deionised water (Millipore) immediately before

loading into the vacuum chamber. This was to reduce the effect of any

insulating layer of silicon oxide (SiO2) on the film.

For the majority of

experiments, electrical conduction through the substrate was not desirable.

This was prevented by the use of undoped silicon substrates (as undoped silicon

exhibits high electrical resistivity) and a variable doping profile in the

diamond film (with a higher resistance region in the diamond adjacent to the

substrate).

2.9 Electrical Contacts to

the films

Four types of electrical

contact were used.

2.9.1 Indium/Gallium Eutectic

Early work with highly doped

films ([C]/[B] ratio of 28,000 to 33,000 p.p.m.) in the gas phase) used

uniformly doped diamond films grown on heavily doped, conductive silicon (Si)

substrates. Electrical contacts were made to the reverse side of the silicon

using a gallium (Ga) /indium (In) eutectic. The silicon was roughened by

scratching with a diamond scribe and then the liquid eutectic was applied. A

contact was made by pressing a steel backing strip onto the eutectic. This

technique was satisfactory for highly conductive diamond films but was limited

by the need to consider the effects of the liquid contact and the interface

between the silicon and the diamond.

2.9.2 Silver Loaded Epoxy Resin

A simpler contact could be

made via the top of the film. For some highly doped films ([C]/[B] ratio of

3,000 to 33,000 p.p.m.), a satisfactory contact could be made by attaching a

wire to the surface using a silver-loaded epoxy resin (‘silver dag’). The

silver dag was often physically protected by a layer of stronger epoxy resin

adhesive (Araldite Rapid) applied over the contact.

It should be noted that

hydrofluoric acid is an extremely hazardous material and the use of direct

contacts to diamond, rather than through the substrate, removed the need for

hydrofluoric acid treatment of the silicon substrates.

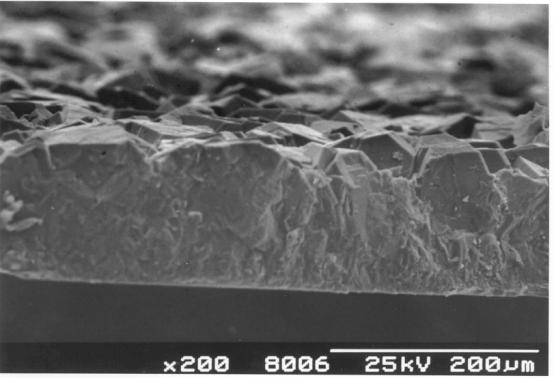

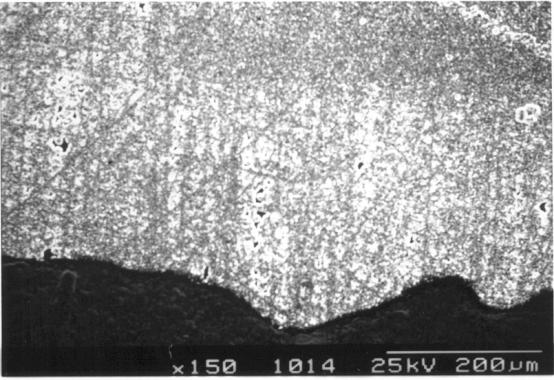

The use of top contacts

allowed greater flexibility in the doping profile of the diamond films. Films

could be grown without the addition of diborane during the early stages of

growth. This would allow nucleation to occur in the absence of boron containing

species. It is not believed that the boron could diffuse significantly through

the film and so the lower portion of the films could be made more resistive

than the upper section. The path of current flow through the films would

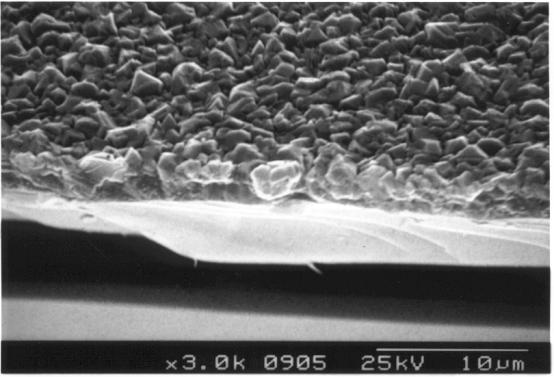

therefore avoid the nucleation side of the film and the substrate material.

This was advantageous because the nucleation side may be considered to be of

lower quality. The nucleation side may be contaminated by species present in

the substrate material and it has an increased number of grain boundaries due

to the nature of the columnar growth method, where diamond growth starts with

many small crystallites which coalesce and form fewer larger domains as the

film grows. This effect could be seen in the cross-sectional SEM image of an

industrial diamond film shown in figure 2.28.

Silver dag contacts did not

give Ohmic behaviour for diamonds with low doping levels ([C]/[B] ratio below

250 p.p.m.) due to a Schottky barrier forming at the metal-semiconductor

interface. 101 Some research groups have argued that

sufficiently electronegative metals such as gold (Au) overcome this

problem 101‑103 but their work remains less than

conclusive.

2.9.3 Three Layer Metalisation

A more reliable way of

forming an Ohmic top contact was to use a “three layer metalization” technique

where three layers of metal were deposited on the surface of the diamond. The

bottom layer was a titanium (Ti) spot which could be annealed to produce a

titanium carbide (TiC) layer between the metal and the diamond. This chemical

bonding reduced the Schottky barrier at the metal-semiconductor interface and

gave the required Ohmic behaviour. A gold (Au) top layer was required to

prevent the oxidation of the titanium during the annealing step and, more

slowly, over the lifetime of the device as titanium reacts readily with any

traces of oxygen at elevated temperatures. Finally, a layer of platinum (Pt)

was required as a barrier layer between the titanium and gold layers to prevent

the interdiffusion of the metals during annealing. Wires could be attached to

the surface of the gold spot using silver dag, as before. A schematic diagram

of the design of the contacts can be found in figure 2.5. Further details of

the formation of Ohmic contacts can be found in chapter 3.

The titanium and gold layers

were deposited using a Edwards evaporator which was modified to incorporate a

heating stage. To prevent oxidation of the titanium, the substrate was heated

in vacuum to remove oxygen containing species from the surface. The titanium

evaporation was then performed on a clean surface. After the deposition, the

sample was allowed to cool down to room temperature before being exposed to

air.

The evaporator worked by

passing a current through a tungsten (W) wire basket containing the source

metal (titanium pellets or short strips of gold). A current of approximately 40

A was sufficient to evaporate the source metal. The substrate, which was

positioned under the basket, became coated by the metal as it resolidified.

Platinum possesses a high

boiling point and could only be evaporated with difficulty. Therefore, a

sputter coater was used to deposit the platinum spots.

|

Element |

Melting Point, qC,m / °C |

Boiling Point, qC,b / °C |

|

Gold (Au) |

1063 |

2970 |

|

Titanium (Ti) |

1675 |

3260 |

|

Platinum (Pt) |

1769 |

4530 |

|

Tungsten (W) |

3410 |

5930 |

Table 2.4 - Transition temperatures

of selected pure metals at standard pressure

Values taken from reference

12 and based upon IUPAC(1983) standards

Figure 2.5 - A schematic

diagram of a three layer metal top contact (not to scale)

Note that the plan view shows the metal layers in reverse order for

illustrative purposes. The layers from top to bottom are Ag, Au, Pt & Ti

The three layer metalization

described above is the best technique used to form good Ohmic contacts to

diamond electrodes. However, the need for three separate metal depositions and

an annealing step reduce the practicality of the technique significantly. The

extensive processing may also effect the surface properties of the film.

2.9.4 Titanium Contacts

A novel method was developed

to form Ohmic contacts for the low doped diamond samples in this study. A

single strip of titanium was deposited onto the surface of the silicon

substrate before the diamond deposition. Selective diamond growth on top of

this metal layer was achieved by leaving a smooth section of silicon which

provided few nucleation sites. As the diamond formed at raised temperatures, a

metal carbide would form without the need for a separate annealing step after

the growth process and, since the film was being grown in the absence of an

oxygen containing species, no protective metals were needed to prevent

oxidation of the titanium. A schematic diagram of the design of the contacts

can be found in figure 2.6. Full details of the technique can be found in

chapter 3.

This technique greatly

simplified the processing required to fabricate a working electrode. The

platinum and gold deposition steps and the annealing process were no longer

required. The titanium deposition could be performed on the substrate before

the diamond deposition. For the three layer metalisation technique, all four of

these steps involved heating the samples above room temperature and so had the

potential to change the surface conditions of the diamond films.

The reduction of the number

of steps significantly reduced the time required to produce a working electrode

and the reliability of the overall fabrication process was dramatically

increased.

The use of a back contact

gives the maximum possible surface area for use as an electrode but requires

the film to be conductive throughout its bulk.

The presence of the titanium

strip made the use of post-treatments more complicated. Procedures such as

refluxing in nitric acid (HNO3) or dipping into chromic acid

(sat. soln. of K2Cr2O7 in conc. H2SO4)

could not be easily performed. This problem could be avoided by the use of PTFE

cells to mark out an area of the diamond film for selective post-treatment.

Figure 2.6

A schematic diagram of a

single layer metal bottom contact (not to scale)

Zone A is a region of diamond growth on bare silicon.

Zone B is a region of diamond growth on titanium coated silicon.

Zone C is a region of titanium coated silicon where the growth of a

continuous diamond film has been prevented by not abrading the silicon prior to

the titanium deposition.

2.9.5 Summary

The advantages and

disadvantages of the four types of contact are summarised below in table 2.5.

|

Type of Contact |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Indium/Gallium |

· does

not effect diamond film · flexibility with post- and pre-treatments · relatively convenient · no reduction in available surface area |

· need to consider diamond-silicon interface · liquid contact - less reliable · HF dip required |

|

Silver Dag |

· very convenient · does

not affect diamond film · flexibility with post- and pre-treatments |

· Schottky barriers |

|

Three Layer Metalisation |

· reliable Ohmic contacts formed |

· diamond film must be heated · time consuming · complicated - risk of failure · limits

on possible |

|

Titanium Underlayer |

· reliable Ohmic contacts formed · does

not affect diamond film · no reduction in available surface area |

· restricted post-treatments · need

to conduct through the entire depth of diamond sample |

Table 2.5 - Summary of the types of electrical contacts used

in this study

2.10 Typical Growth Conditions

Table 2.6 summarises the

typical growth conditions for the diamond films. Appendix B gives full details

of the growth conditions for the films used in these studies.

|

Pressure |

20

Torr |

|

Hydrogen

flow rate |

200

s.c.c.m. |

|

Methane

flow rate |

1.4

s.c.c.m. |

|

Diborane

flow rate (range) |

5

´ 10-6 s.c.c.m. to 5 ´ 10-2 s.c.c.m. |

|

Diborane

flow rate (typical of low end) |

4

´ 10-5 s.c.c.m. |

|

Substrate

temperature |

900

ºC |

|

Filament

temperature |

2400

ºC |

|

Filament/substrate

separation |

4

mm |

|

Deposition

Time |

7

hours to 27 hours |

|

Substrates |

Si

- see appendix B for specifications |

|

Filaments |

two

ten-turn Ti coils |

Table 2.6 - Typical

deposition conditions for the hot-filament CVD reactor

2.11 Secondary Ion Mass Spectroscopy

Secondary Ion Mass

Spectroscopy (SIMS) was used to detect the presence of boron in the films and

to determine the level of doping.

SIMS involved the

bombardment of the sample with high energy ions in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV)

chamber. On impact with the sample, the incident ions caused the ionisation of

the surface. The ions released from the surface entered an electric field which

drew them into a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (ToF‑MS). The time

taken for the ions to reach the detector was proportional to the ratio of the

mass of the ion to its electronic charge (m/z).

SIMS analysis of the diamond

films grown for this study was performed at two institutions: the University of

Bristol Interface Analysis Centre (IAC) and Millbrook Instruments Limited

(Lancashire).

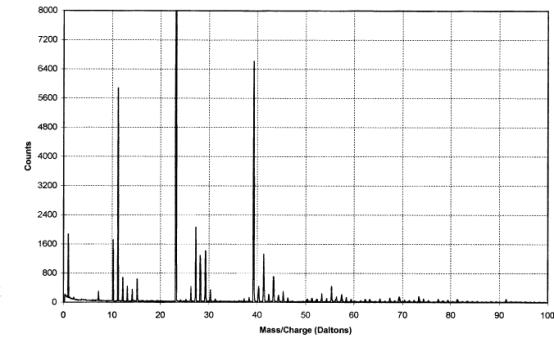

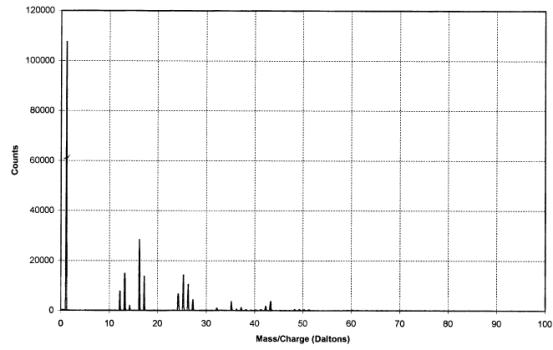

The IAC produced positive

and negative ion spectra (figures 2.7 and 2.8 respectively). The positive ion

spectrum showed peaks at m/z values of 10 and 11 daltons. This

corresponded to singly charged ions of the two isotopes of boron (10B+

& 11B+) and indicated the presence of boron in the

films. Unfortunately, without knowledge of the relative sensitivity of the

technique to the different species present, the data can not be used for

quantitative analysis of the boron concentration.

Figure

2.7 - A positive ion time-of-flight SIMS spectrum

Figure

2.8 - A negative ion time-of-flight SIMS spectrum

Four diamond samples were

sent to Millbrook Instruments for SIMS analysis. Table 2.7 shows the relevant

characteristics of the films.

Sample |

Code Number |

Concentration of boron in the gas phase [B]/[C] in p.p.m. |

Comment |

Resistance (W) |

|

(a) |

B4 |

undoped |

grown before first use of

boron containing species |

2.5 ´ 106 |

|

(b) |

B47 |

“low” |

boron contamination from

chamber |

2500 |

|

(c) |

B48 |

8.8 ´ 10-5 |

|

250 |

|

(d) |

B44 |

5.3 ´ 10-3 |

|

600 |

Table 2.7 - Samples analysed

by Millbrook Instruments using SIMS

The resistance values given

were determined using a digital voltmeter (DVM) and were intended for use only

as rough guidance.

Millbrook Instruments

provided a laboratory standard graphite sample with a known concentration of

boron (50 p.p.m.). This allowed for calibration of the spectra.

Figures 2.9 to 2.12 show the

raw spectra for the four diamond samples and figure 2.13 shows the

corresponding figure for the graphite control. The processed data are shown in

figure 2.14. The analysis conditions are summarised in table 2.8 below.

Incident

Ion |

Ga+ |

|

Beam

Intensity |

6

keV, 20 nA |

|

Raster

Area |

250

mm ´ 250 mm |

|

Mass

Range |

6

- 16 m/z (10 channels per mass) |

|

Dwell

Time |

1

second per channel |

|

Averaging |

10

scans |

|

Acquisition

Time (per spectrum) |

1000

seconds |

Table 2.8 - A Summary of the

SIMS Experimental Conditions

Figure 2.9 - A positive ion

time-of-flight SIMS spectrum of sample (a)

Figure 2.10 - A positive ion

time-of-flight SIMS spectrum of sample (b)

Figure 2.11 - A positive ion

time-of-flight SIMS spectrum of sample (c)

Figure 2.12 - A positive ion

time-of-flight SIMS spectrum of sample (d)

Figure 2.13 - A positive ion

time-of-flight SIMS spectrum of the graphite control

Figure 2.14 - SIMS spectra plotted relative to the undoped control

sample (a)

Adsorbed oxygen and water

enhanced the B+ signal by an order of magnitude. However, long count

times had to be employed to detect the low levels of boron and the surface was

significantly eroded. Therefore, the enhanced signal intensity at the surface

did not give a reduction of the detection limit.

As expected, samples (b),

(c) and (d) showed boron peaks at m/z values of 10 and 11. The ratio of the

intensities of the two boron peaks ranged from 80:20 to 70:30 which is in

agreement the ratio of natural abundances of the boron isotopes 10B

and 11B (81.3 : 18.7). 12

The peaks at m/z

values of 12, 13, 14 and 15 corresponded to CHx+ ions where x = 0 to 3.

Samples (a), (b) and (d) all showed a low level

contaminant peak at m/z = 7. This corresponded to lithium ions

(Li+). The intensities of the peaks indicated that the lithium

contamination was at the sub p.p.m. level.

The results suggested that the level of doping in

the films is broadly proportional to the gas phase concentrations. Previous

published work using SIMS to analyse levels of boron doping in CVD diamond had

been inconclusive. 79,104,105

As SIMS is a locally

destructive technique, it may be used to produce depth profiles where the

concentrations of the species are plotted against the depth of erosion into the

sample. Depth profiling requires long measurement times and so proved

impractical due to the hardness of diamond and its resistance to erosion.

However, in the experiments detailed here, the low levels of boron in the films

necessitated the sampling of a sufficiently large quantity of material in order

to produce reliable results that the values may be considered to apply to the

bulk rather than the surface.

It should be noted that SIMS measures the total

boron content in the films. This boron does not necessarily have to occupy

electrically active substitutional sites in the diamond crystal.

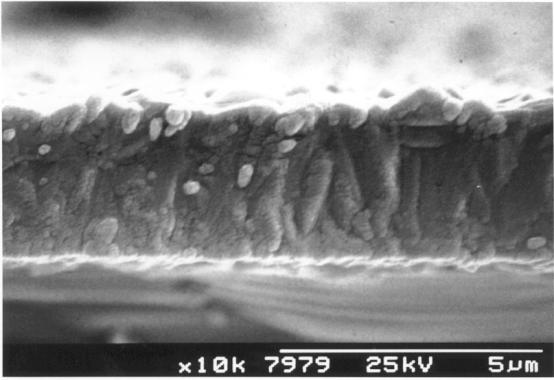

2.12 Scanning Electron Microscopy and Optical

Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy

(SEM) and optical microscopy were the main techniques used to characterise the

films.

The SEM work was performed

on a Hitachi Model 3200 Scanning Electron Microscope operating with an

accelerating potential of 25 keV. A Mamiya camera loaded with rolls of 6 ´ 7 cm film was used to capture images.

SEM requires samples that

are electrically conductive. In order to increase the surface conductivity of

insulating samples, a layer of gold (Au) was deposited with an Edwards S150A

Sputter Coater. This treatment was not required for the boron doped diamond

samples as the doping made them sufficiently conductive.

The electron microscope was

fitted with an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer designed to perform

an elemental analysis. The EDX detector was protected by a beryllium (Be)

window. This prevented the detection of X-rays from elements with low atomic

numbers such as carbon (C) and boron (B) and so the EDX spectra were of limited

use in the analysis of the boron doping of diamond.

A Zeiss Axiolab Optical

Microscope fitted with Zeiss Epiplan lenses was routinely used to view the

samples. Objective lenses of 5 ´, 10 ´, 50 ´ and 100 ´ coupled with an 10 ´ eyepiece to give a range of magnifications

from fifty to one thousand.

Images were captured with a

JVC TK-1280E Colour Camera attached to an Olympus BH2 Optical Microscope fitted

with a 10 ´ eyepiece and 4 ´, 10 ´, 20 ´ and 50 ´ objective lenses.

Optical microscopy was

particularly helpful in monitoring the deposition of titanium. Titanium layers

that had become oxidised were often blue in colour.

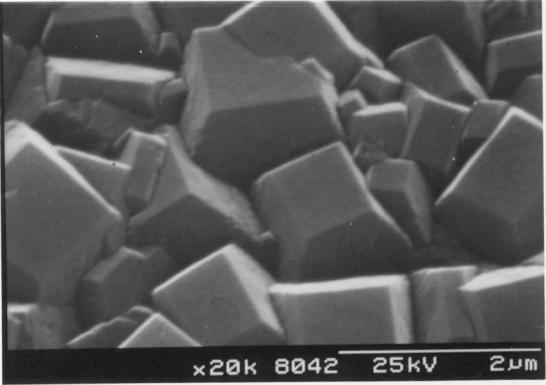

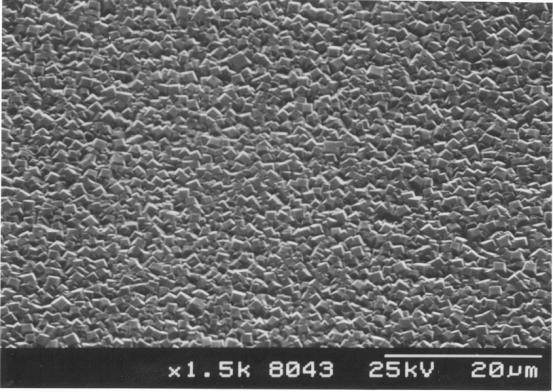

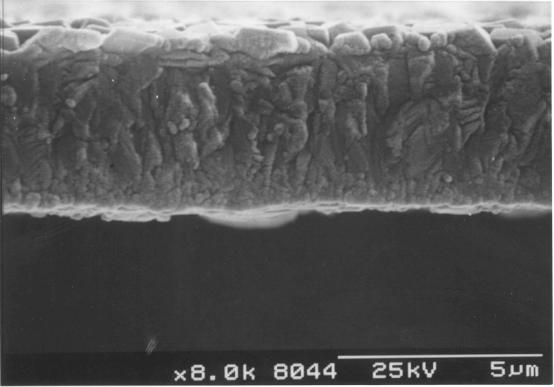

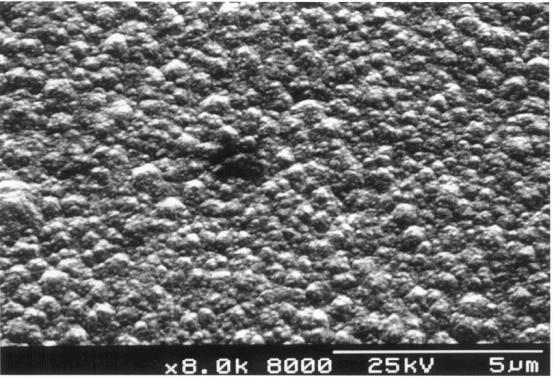

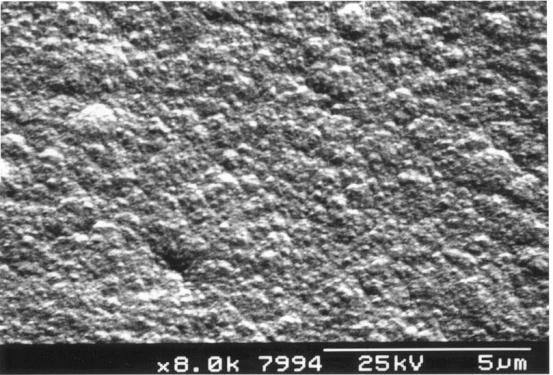

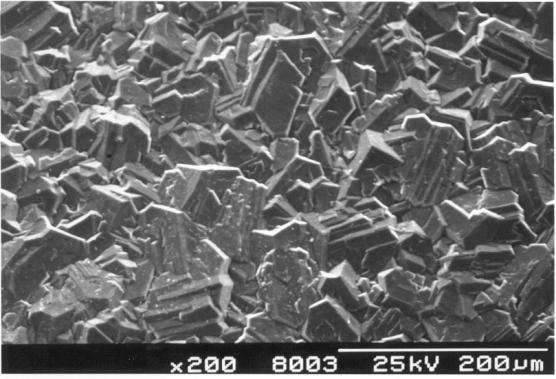

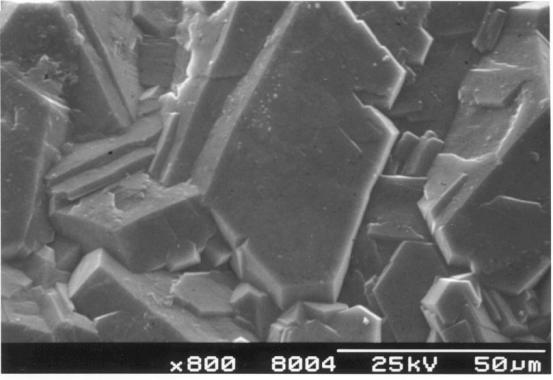

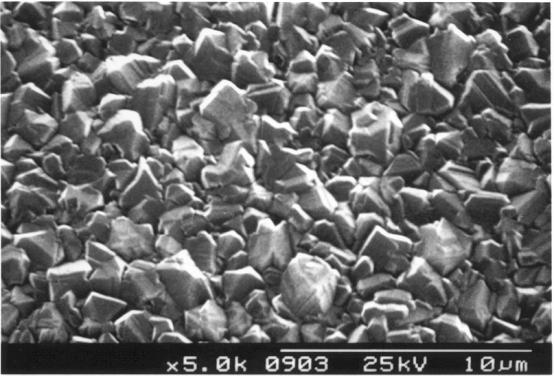

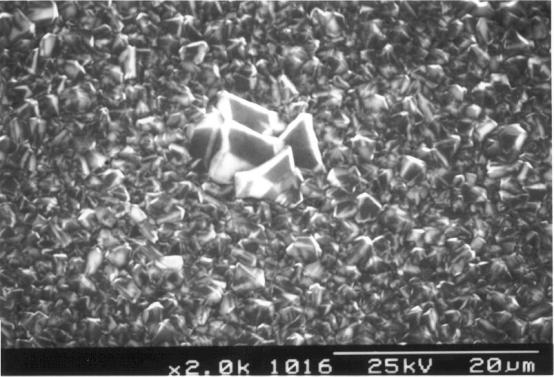

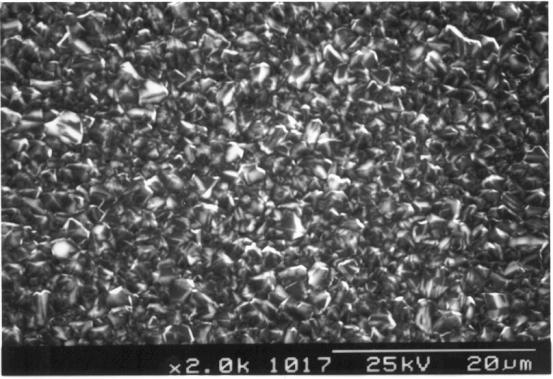

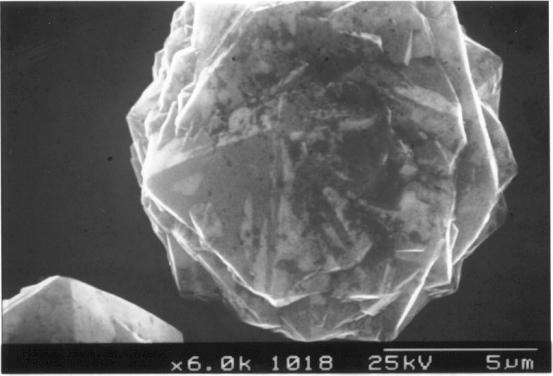

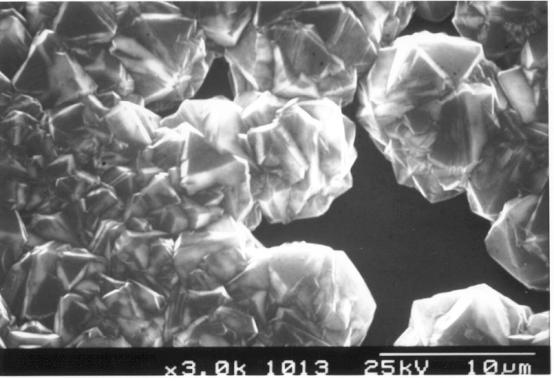

SEM and optical microscopy

showed the diamond films to be continuous and composed of well formed

crystallites. Initial experiments were performed in which the growth conditions

were varied. These confirmed that the optimum growth conditions outlined in

previous studies gave the best results. Figures 2.15 to 2.18 show SEM images of

an undoped diamond film grown under the typical conditions listed in table 2.6.

Figures 2.15 to 2.17 show images of the top surface at various levels of

magnification. Figure 2.18 shows a image of the cross-section of the film. The

film was uniform and has well defined, predominantly square faceted

crystallites.

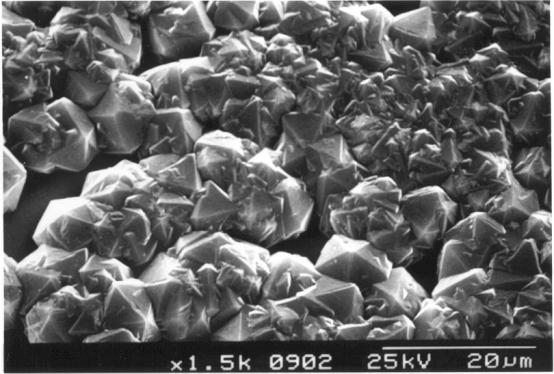

Figures 2.19 and 2.20 show

diamond films grown with double and quadruple the normal concentration of

methane respectively. The films exhibited a much less well defined structure,

characteristic of growth with a high carbon to hydrogen ratio in the gas

mixture. 14,17

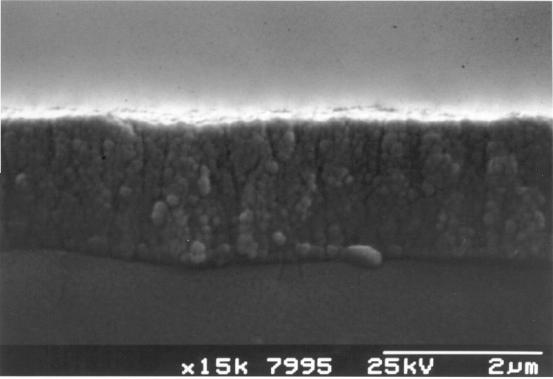

Figures 2.21 and 2.22 show

cross-sectional SEM images typical of those used to measure the thickness of

the diamond films. The rate of deposition, calculated by dividing the thickness

of the diamond by the growth time, varied between films from zero to 0.7 mm/hr.

Within each growth run, the

rate of deposition was expected to vary. Initial nucleation had to occur before

a continuous film could start to form. Growth would then progress on different

crystal faces at different rates. The gradual reaction of the hot filaments or

any other changes in the reaction conditions may have added to any variations

in the rate of growth.

The thickness of thirty

samples, which had grown beyond the nucleation phase and formed continuous

films, was measured. The mean growth rate was 0.3 ± 0.2 mm/hr. No significant

difference in the rate of deposition was detected between boron doped and

undoped diamond films.

Figure

2.15 - The surface of a HFCVD diamond film showing

square

facets and a twinned crystallite [sample B13]

Figure 2.16

- The surface of a HFCVD diamond film [sample B13]

Figure 2.17 - The surface of a HFCVD

diamond film

showing

uniform coverage over the substrate [sample B13]

Figure

2.18 - A cross-section of a diamond film [sample B13]

Figure 2.19 - A

diamond film grown in an atmosphere containing 1.4% methane

(double

the normal concentration) [sample B6]

Figure 2.20 - A

diamond film grown in an atmosphere containing 2.8% methane

(quadruple

the normal concentration) [sample B8]

Figure 2.21 - A

cross-sectional view of a diamond film grown with quadruple

the normal

concentration of methane in the gas phase [sample B8]

Figure 2.22 - A

cross-sectional view of the results of an early growth run

[sample

B1]

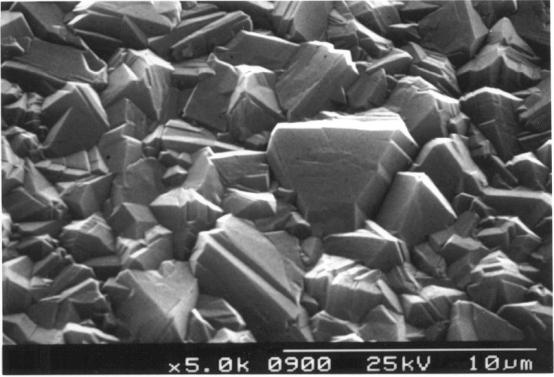

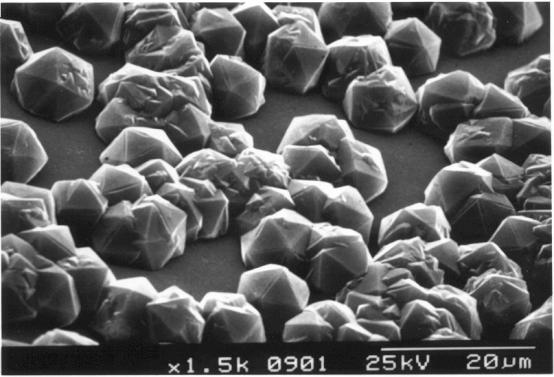

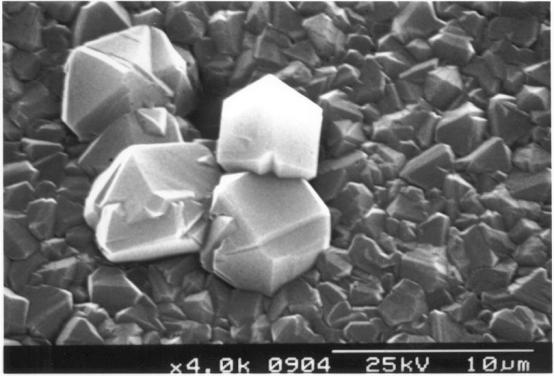

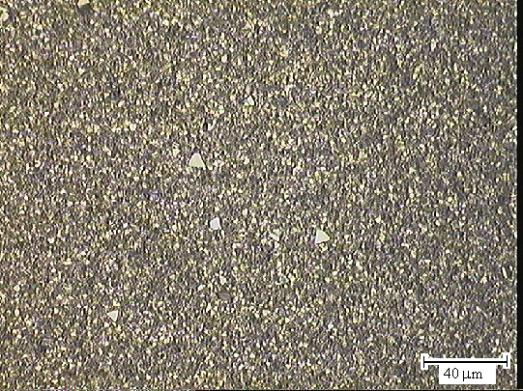

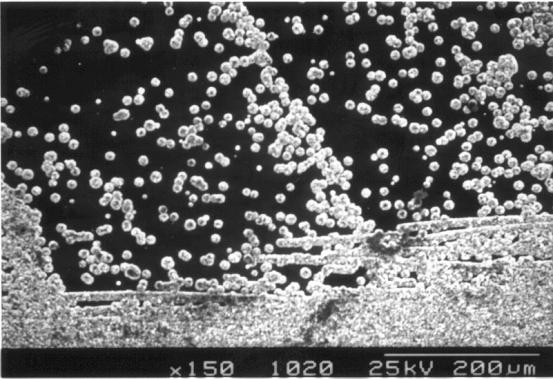

Figures 2.23 to 2.25 show

images of a sample where the diamond growth had been stopped after 5 hours and

35 minutes. Figure 2.23 shows the surface at the centre of the sample where the

diamond film was continuous with well defined facets. Figures 2.24 and 2.25

show the surface at the periphery of the sample where the growth has not

progressed far beyond the nucleation stage, leaving individual crystallites on

the silicon substrate.

The quality and morphology

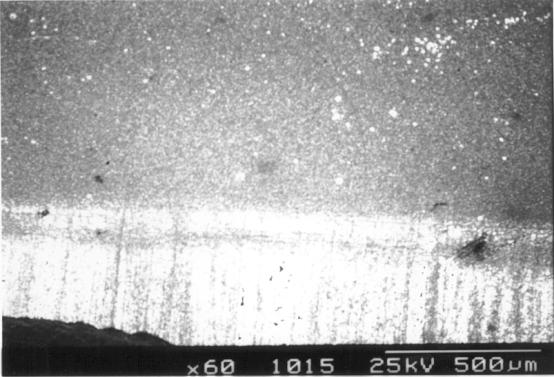

of the films was comparable to that obtained in industrially grown samples.

Figures 2.26 to 2.28 show an industrial free-standing diamond film that was

grown for an optical application in the aerospace industry using microwave

plasma assisted CVD (MPACVD). 106 The industrial film was grown

continuously for about ten days 107 and is therefore much thicker

(175 mm) than the HFCVD films and it exhibits

larger facet sizes (~50 mm).

Figures 2.29 and 2.31 show

various views of a thin diamond film.

Figure

2.23 - A continuous diamond film [sample B142a]

Figure 2.24 -

Incomplete surface coverage at the edge of a thin diamond film.

The silicon substrate

was visible behind the diamond crystallites [sample B142a]

Figure 2.25 - The

reaction stopped at the stage where the individual crystallites

have

started to coalesce to form a continuous film [sample B142a]

Figure

2.26 - Industrial MPACVD diamond (undoped)

Figure

2.27 - Industrial MPACVD diamond (undoped)

Figure

2.28 - A cross-section of a free-standing industrial

MPACVD

diamond film

Figure 2.29 - SEM

image showing large crystallites formed around 2-3 mm

diamond

crystals remaining from the substrate abrasion process [sample B141b]

Figure

2.30 - SEM image showing growth of a thin diamond film

[sample

B141b]

Figure 2.31 -

SEM image showing a cross-section of a thin diamond film

[sample

B141b]

The titanium contacts

described in section 2.9.4 required three distinct zones of diamond growth.

·

The

main section of the sample had to comprise of a continuous film of high quality

diamond grown directly over an insulating silicon substrate. This zone would

form the electrode surface in the electrochemical experiments.

·

An

exposed titanium strip was required at the edge of the sample to allow

electrical connections to be made.

·

Finally,

a middle zone is required comprising of diamond grown over titanium. This zone

would form the Ohmic contact between the metal and the semi‑conducting

diamond.

The standard electrode

design had a single strip of titanium (as shown in figure 2.6). This was

ideal for the electrochemical studies as the design maximised the surface area

of usable diamond. The single strip design did not, however, readily facilitate

studies of the contact itself. The absence of a second Ohmic contact

complicated measurements of the current-voltage characteristics. To avoid this

problem, a diamond sample was made with two titanium strips, on opposing edges

of the sample, as shown in figure 2.32. The electrical properties of this film

were investigated as detailed in chapter 3.

Figures 2.33 to 2.60 show

SEM and optical images of the double ended sample (B147a). The sample has good

coverage where required (zones 2 to 4) and incomplete coverage where the

titanium needs to be exposed (zones 1 and 5). The two end zones were prepared

in the same way: a coating of titanium was applied to a clean, smooth, unabraded

silicon surface. However, the extent of diamond growth on these zones varied

considerably. Zone 5 was typical of growth on unabraded substrates: isolated

crystallites formed with minimal overall coverage. Zone 1 was unusual in that

there was much greater coverage than normal. The growth had progressed beyond

the nucleation stage and the crystallites had started to coalesce. The

increased coverage did not, however, provide complete coverage and good

electrical contacts could still be made to the exposed underlying titanium.

Figure 2.32 - A schematic

diagram of sample B147a (not to scale)

Zone 3 is a region of diamond growth on bare silicon.

Zones 2 & 4 are regions of diamond growth on titanium coated

silicon.

Zones 1 & 5 are a regions of titanium coated silicon where the

growth of a continuous diamond film has been prevented by not abrading the

silicon prior to the titanium deposition.

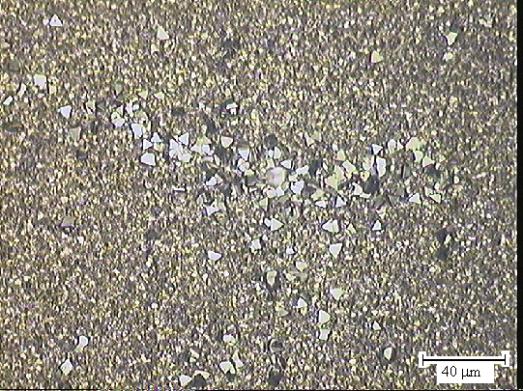

Figures 2.33 to 2.36 show

four optical microscopy images of the central section of the surface (zone 3)

taken with a 50 ´ objective lens. The images

were taken at well spaced points across zone one and show the uniformity of the

film. Figure 2.37 shows a smaller scale image taken with a 20 ´ objective lens. SEM images of zone 3 are

shown in figures 2.38 and 2.39.

As described in section 2.8,

2-3 mm

diamond grit was used in the preparation of the substrates. The majority of the

diamond grit was removed from the silicon surface before the substrate was

loaded into the CVD chamber. Any remaining diamond crystals that survived the

cleaning process acted as nucleation sites for diamond growth. Figure 2.28

shows a SEM image of diamond crystallites formed from such growth. Optical

microscopy clearly showed these crystallites as any facets orientated normal to

the incident light beam would shine brightly as they reflected the light back

towards the optical system. A number of isolated square and triangular facets

can be seen in figures 2.33 to 2.35, while 2.36 shows a conglomeration of them.

Figures 2.34 and 2.37 show complete crystallites, highlighted by red circles,

in which none of the facets are perpendicular to the normal illumination.

Sample B147a contained

larger numbers of these crystallites than were normally seen in the diamond

films. The presence of two titanium strips on the substrate made the abrasion

and cleaning process more complicated. It was necessary when cleaning the

surfaces of the abraded regions (zones 2 to 4) to keep the surfaces of the end

regions (zones 1 & 5) free from diamond grit and so, in order to prevent

contamination, a less rigorous cleaning procedure was performed.

Figures 2.33 & 2.34 - optical microscopy images of the central

section (zone 3),

50 ´ objective lens, red circle

highlights a crystal (see page 67) [sample B147a]

Figures 2.35 & 2.36 - optical microscopy images of the central

section (zone 3)

taken with a 50 ´ objective lens [sample

B147a]

Figure 2.37 - optical microscopy image of the central section (zone 3),

20 ´ objective lens, red circle highlights a

crystal (see page 67) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.39 - SEM image of the central section (zone 3) [sample B147a]

As expected, the growth of diamond

on zones 1 and 5 did not totally cover the underlying titanium.

Zone 5 was typical of the

films grown on smooth titanium covered silicon, in that there was only isolated

diamond growth. Figure 2.40 shows an optical image of the sample taken with a

50 ´ objective lens. The lower left hand side

showed some coalescing of the individual cystallites but the majority of the

area was covered only by well spaced, isolated crystallites. Figure 2.41 shows

a similar image, in which a continuous narrow strip of diamond could be seen,

probably formed along a microscopic scratch on the surface of the silicon.

Figure 2.42 shows an area of

denser coverage nearer the adjacent abraded region (zone 4) and figure 2.43

shows an optical image taken at a lower resolution (20 ´ objective lens). Figure 2.44 and 2.45

show SEM images of zone 1 of the film. The detail of an individual crystallite

can be seen in figure 2.45.

The opposite end of the

sample (zone 1) exhibited unusually good diamond coverage, comparable to the most

extensive growth seen on any of the unabraded titanium strips in this study.

Figures 2.46 and 2.47 show optical images of zone 1 taken with a 50 ´ objective lens and figures 2.48 and 2.49

show the region viewed with a 20 ´ objective lens. Figure 2.50

shows an SEM image of zone 1. The images show that although there was

considerable diamond coverage, there were still areas of exposed titanium. Good

electrical contact could therefore be made to this region.

Figures 2.40 & 2.41 - optical microscopy images of one of the end

sections

(zone 5) taken with a 50 ´ objective lens

showing limited diamond growth [sample B147a]

Figure 2.42 - optical microscopy image of taken with a 50 ´ objective lens

showing partial diamond growth [sample B147a]

Figure 2.43 - optical microscopy image of one of the end sections (zone

5)

taken with a 20 ´ objective lens [sample

B147a]

Figure 2.44 - SEM image of one of the end sections (zone 5) [sample

B147a]

Figure 2.45 - SEM image of one of the isolated diamond crystallites

[sample B147a]

Figures 2.46 & 2.47 - optical microscopy images of one of the end

sections

(zone 1) taken with a 50 ´ objective lens showing

partial diamond growth

[sample B147a]

Figures 2.48 & 2.49 - optical microscopy images of one of the end

sections

(zone 1) taken with a 20 ´ objective lens showing

partial diamond growth

[sample B147a]

Figure

2.50 - SEM image of one of the end sections (zone 1)

showing

partial diamond growth [sample B147a]

The boundaries between the

growth zones can be seen in figures 2.51 to 2.57 (optical microscopy) and

figures 2.58 to 2.60 (SEM).

Figures 2.51, 2.52 and 2.58

show the clearly defined boundary between zones 4 and 5.

Figures 2.51 and 2.58 show

the same region viewed by optical and electron microscopy respectively.

Measurement of the distances between distinctive features visible in both the

images allowed an accurate scale to be applied to the optical images presented in

this chapter.

Figures 2.53 and 2.54 show

the boundary at the opposite end of the sample (between zones 1 and 2). There

was less difference between the diamond coverage in these two zones but the

boundary could still be identified.

Figure 2.55 shows the

boundary between zones 3 and 4. There is complete diamond coverage over both

regions. The transparency of the diamond film allowed light to pass through the

sample. Zone 4 appeared brighter than zone 3 as the titanium beneath zone 4

reflected more light than the silicon beneath zone 3.

Figures 2.56 and 2.57 show

the boundary between zones 2 and 3. As for the boundary between zones 3 and 4,

the diamond coverage was complete and reflection from the underlying titanium

could be seen.

Figures 2.59 and 2.60 show

SEM images of the boundary between zones 1 and 2. Zone 2 can be seen at the top

of the images with zone 5 beneath it. The dark areas at the bottom of the

images showed the silver dag which had been used to make electrical contacts to

zone 1.

Figure 2.51 - the boundary between zones 4 and 5 (´ 20 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.52 - the boundary between zones 4 and 5 (´ 10 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.53 - the boundary between zones 1 and 2 (´ 10 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.54 - the boundary between zones 1 and 2 (´ 10 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.55 - the boundary between zones 3 and 4 (´ 20 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.56 - the boundary between zones 2 and 3 (´ 20 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure 2.57 - the boundary between zones 2 and 3 (´ 10 lens) [sample B147a]

Figure

2.58 - SEM image of the boundary between zones 4 and 5

[sample

B147a]

Figure

2.59 - SEM image of the boundary between zones 1 and 2

[sample

B147a]

Figure

2.60 - SEM image of the boundary between zones 1 and 2

[sample

B147a]

2.13 Laser Raman Spectroscopy

Raman Spectroscopy is a well

established diagnostic technique for determining the quality of diamond films. 108-112

Spectra of diamond show a characteristic peak at a shift of 1332 cm-1

relative to the excitation wavenumber. The peak is the highest energy Raman

peak for diamond and corresponds to the zero phonon excitation in the crystal.

In good quality diamond samples, this peak is sharp. However, if the crystal

structure is distorted then the spread of the peak, as measured by the

full-width half-maximum, will increase and the peak may be shifted up or down

the spectrum.

As well as the diamond peak

at 1332 cm-1, a number of other Raman peaks may be seen in poor

quality diamond films. Graphite produces peaks at 1580 cm-1 and

1355 cm-1 and disordered sp2 carbon produces an

asymmetrical broad band from 1100 cm-1 to 1600 cm-1 with

a maximum at around 1520 cm-1.

Raman spectroscopy can be a

very sensitive technique in detecting small amounts of graphitic content in

diamond films. When the incident laser beam with an excitation wavelength of

488 nm is chosen, the technique is fifty times more sensitive to sp2

structures than to sp3 structures.

In addition to Raman peaks,

the laser illumination can also lead to photoluminescence (PL) peaks due to

impurities and structural defects.

Raman spectroscopy provides

an excellent tool to gain qualitative information on the quality of diamond

films.

Several studies have reported

changes to the Raman spectrum due to the presence of boron in the diamond

films. These changes require higher levels of doping than can be those present

in the films presented here

(50 p.p.m., 9 ´ 1018 B atoms/cm3).

Raman spectra were taken with

a Renishaw Raman Imaging Microscope and Spectrometer with a spectral resolution

of 1 cm-1. An argon gas laser with a wavelength of 488 nm (green

light) was used to provide the incident laser beam.

Figure 2.61 shows a Raman

spectrum of a natural type IIb diamond crystal.*

A single sharp peak can be seen which was used to calibrate the spectrometer.

Figure 2.62 shows a Raman

spectrum of an poor quality undoped diamond film grown by MPACVD which provides

an example of some of the features that may be seen in diamond films. The 1332

cm-1 diamond peak is visible but is not particularly sharp and not

larger than the other features. A broad peak centred around 1355 cm-1

due to graphite and disordered sp2 carbon and a broad band centred

at around 1500 cm-1 can be seen. The broad band shows some fine

structure that may be due to impurities or defects (such as nitrogen centres).

The fine structure can not be readily assigned from a spectrum taken at room

temperature.

Figures 2.63 to 2.68 show

Raman spectra of diamond films grown for this study. While there was some

variation in the spectra, they all displayed a sharp 1332 cm-1

diamond peak. There was some evidence of a broad band due to disordered sp2

carbon but this was weak and therefore confirmed that there was little sp2

carbon present in the films.

zero‑phonon

peak and no other significant features

Figure 2.62 - Raman spectrum of a poor quality undoped MPACVD

diamond

film

Figure 2.63 - Raman spectrum of boron doped diamond [sample B128a]

Figure 2.64 - Raman spectrum of boron doped diamond [sample B128b]

Figure 2.65 -

Raman spectrum of boron doped diamond [sample B129a]

Figure 2.66 - Raman spectrum of boron doped diamond [sample B130b]

Figure 2.67 - Raman spectrum of boron doped diamond [sample B140a]

Figure 2.68 - Raman spectrum of boron doped diamond [sample B140b]

2.14 Summary

CVD apparatus has been

assembled which can deposit boron doped polycrystalline diamond films with a

wide range of doping levels.

SIMS, SEM and optical

microscopy have been used to show the films to be continuous and of high

quality.

Diamond films have been

deposited selectively onto patterned silicon wafers. The use of patterned

silicon wafers with a partial titanium covering provided a novel method to

fabricate boron doped diamond films with good Ohmic contacts.

† Chromic acid was prepared immediately before use by making a saturated a saturated solution of potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) in concentrated sulphuric acid (H2SO4). 134

† The manufacturer of the diborane gas used in these studies required approximately six months to produce and deliver a standard order of diborane. Supplies of more esoteric gases, such as the trimethylboron (B(CH3)3) used in references 76 and 77 were not as readily available.

‡ Vaporisation has been used as an alternative to dissolution for solid B2O3 sources 92 but problems with controllability remain.

* Type II is a classification established in 1934 for diamonds transparent to 8 mm infra-red radiation. It was subsequently discovered that the diamonds that are opaque to 8 mm radiation, and hence classified as type I, contain nitrogen impurities. 5 Type IIb signifies a very low concentration of nitrogen.