DNA

It is now 50 years since the groundbreaking work on the structure of DNA was published and it seems appropriate to reflect on controversy surrounding the role of Rosalind Franklin in the discovery of the Double Helix.

Picture 3

‘There is a myth, owing its origins to James Watson’s caricature in The Double Helix, that Rosalind Franklin was an uncooperative, prickly, bad tempered bluestocking who hoarded her data. The feminist counterpart to this mythology is that she was a woman who was underrated and patronised by many of her male colleagues and deprived by the prevailing misogyny of the recognition she so richly deserved’ Bridges, 2000.

Rosalind Franklin was born into a wealthy family. She was educated at St. Paul’s Girls School (London) and Newham College, Cambridge. On leaving Cambridge in 1942, Rosalind joined the British Coal Utilization Research Association where she worked on the structure of carbons. In 1947 she left England for Paris where she worked for four years as a researcher at the Laboratoire Central des Services Clinique de L’Etat (Piper, 1998).

On her return to London she took up a post at King’s College having been appointed by Sir John Randall, professor of Physics and Director of the MRC Biophysics Research Unit. It was her understanding that she was to set up and expand a new X-ray diffraction unit. As Piper (1998) recalls Maurice Wilkins was on holiday on the day of her appointment. When he returned he assumed she was to assist his work. It was only years later that Wilkins saw her letter of appointment and this did not clearly define the nature of her responsibilities. Furthermore, Wilkins and Franklin had significant personality differences - Franklin direct, quick, decisive, and Wilkins shy, speculative and passive. This caused a lot of tension between them. Furthermore, Franklin discovered that the senior Common Room at King’s was closed to women!

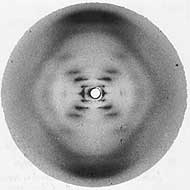

By early 1953, Rosalind Franklin had discovered that there were two forms of the helix, which she named A and B. It is the B-form that marks the controversy of her role in the discovery of the structure of DNA. Franklin had an excellent photograph of the B-form which she passed to Wilkins. Days later Watson visited King’s. Wilkins, being temporarily unavailable, Watson called in on Rosalind. Piper (1998) notes, ‘What exactly happened then is not entirely clear, but apparently they almost came to blows before Wilkins arrived and took Watson away’. Shortly afterwards Wilkins showed Rosalind’s B-form photograph.

Rosalind’s draft paper on March 1953 outlined her position that the B-form was helical comprising two coaxial chains. Watson and Crick came to the same conclusion but were ready to publish (Watson and Crick, 1953).

The resolution of the B-form photograph #51 shown in the figure allowed Franklin to determine that each turn of the helix in the B form is 34 Å long and contains 10 base pairs separated by 3.4 Å each.

Picture 4

Rosalind's unpublished conclusions where presented at a routine seminar,her work was then provided to Watson and Crick at Cambridge University.

When Watson saw Rosalind's photograph 51 (above), the solution became apparent to him, and with data from other scientists Watson and Crick where able to prepare their ultimately correct and detailed description of DNA's structure in 1953. The article was published in Nature and Rosalind published a supporting article in the same issue of the journal. Rosalind was also very close to discovering the structure herself but was beaten to it in a large part because of the friction between Wilkins and herself. The following year she moved to J. D. Bernal's lab at Birkbeck College, where she worked on the tobacco mosaic virus. She also began work on the polio virus. However in the summer of 1956, Rosalind became very ill with ovarian cancer. She died less than two years later.

In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins received the Nobel prize for the discovery of DNA. Although Rosalind Franklin had already died and Nobel prizes aren't given out posthumously it is unknown if she had lived would she have gotten any credit.

Reference for this page only:

Watson, J.D. and Crick, F. H.C. (1953), Nature, 171, pp. 737-738