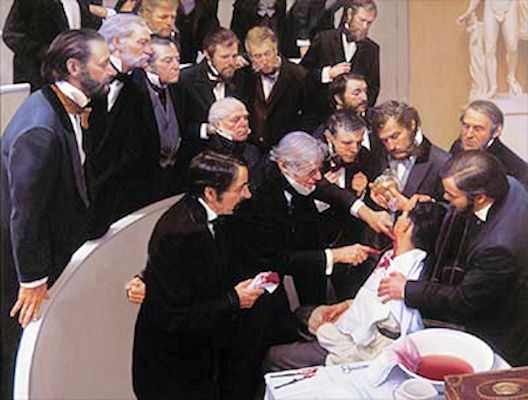

A doctor in the late 1800s administering ether before surgery

![]()

Diethyl ether

The well-known anaesthetic

![]()

![]()

Molecule of the Month September 2023

Also available: JSMol version.

![]()

A doctor in the late 1800s administering ether before surgery |

Diethyl etherThe well-known anaesthetic

Molecule of the Month September 2023

|

Yes, ‘ether’ is just a common abbreviation for this particular chemical. But to a chemist, ‘ether’ is also a generic name for the group of organic molecules which contain an oxygen atom which links two alkyl or aryl groups together, in the form R1-O-R2. The R groups can be CH3-, C6H5- or any organic fragment, and if R1=R2 then the ether is said to be symmetrical. The simplest ether is dimethyl ether (CH3-O-CH3) which is a colourless gas that is used as an aerosol spray propellant and has been suggested as a potential renewable alternative fuel for diesel engines. In the case of diethyl ether, both R grouplinks two alkyl or aryl groups togethers are ethyl groups, giving the formula CH3-CH2-O-CH2-CH3.

|

Diethyl ether |

Actually, the word ‘ether’ (sometimes spelled ‘aether’) can be traced back to the Greek philosopher Aristotle (ca. 4 BC) who proposed that as well as the four classical elements: earth, fire, water, and air, there should be a fifth element, aether, that made up the stars and planets. This idea of the existence of a substance all around us was later adopted by scientists trying to explain how electromagnetic or gravitational forces could propagate through space. Isaac Newton described light passing through an ‘aethereal medium’ being the reason for refraction, while James Clerk Maxwell developed his model of electric and magnetic phenomena based on them being transmitted through a ‘luminiferous aether’. However, the concept of an ether was disproved in the late 1800s, although the idea is still in use in general parlance to mean the undefined region of space around us (e.g. Radios send messages through the ether, or My email didn’t arrive – it must have been lost in the ether).

The first ether to be discovered was diethyl ether, which was synthesised in 1540 by the German botanist Valerius Cordus by distilling a mixture of ethanol and sulfuric acid (then known as oil of vitriol). He called his discovery "sweet oil of vitriol" (oleum dulce vitrioli). Around the same time, the Swiss physician Paracelsus, experimenting on dogs, discovered that this oleum dulce vitrioli acted as a painkiller. But it wasn’t until 1729 that the German chemist August Sigmund Frobenius provided the first detailed description of its properties and renamed it Spiritus Vini Æthereus, meaning ‘ethereal spirit of the wine’ (because the ethanol from which it was made came from distilling wine). ‘Ethereal’ here described the volatile nature of the liquid, which rapidly turned into a vapour even at room temperature. His first article about ether in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society contains some amusing descriptions of his experiments:

[Taken from: An Account of a Spiritus Vini AEthereus, Together with Several Experiments Tried Therewith, Dr. Frobenius,

Phil. Trans. (1683-1775), 1729-1730, Vol.36 (1729-1730), pp.283-289, available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/103540]

Diethyl ether is known to most people because of its anaesthetic effects. But these were discovered by accident due to ether being used recreationally in ‘ether frolics’.

These came about after scientists and medics heard reports of the ‘nitrous oxide capers’ that were occurring in England in the early 1800s, following the discovery of nitrous oxide (laughing gas, MOTM June 1999). These ‘capers’ often took place in travelling medicine shows and carnivals, where the public would pay to inhale a minute's worth of the gas. People would laugh and behave strangely until the effect of the drug ended, when they would stand about in confusion. The famous chemist Sir Humphry Davy used to put on such displays for the renowned people and dignitaries of that time.

Parties and 'frolics' fuelled by nitrous oxide and ether were common in the 1800s.

Yes - when inhaled in small amounts (i.e. not to the extent of unconsciousness), ether has a similar effect as nitrous oxide - it produces a sense of exhilaration and light-headedness. As a result, ‘ether parties’ and ‘ether frolics’ came into fashion in the mid-1800s in America, in which guests would sniff ether together to get high. These frolics were socially acceptable, even for the medics and pharmacists who provided the ether. Reports from that time say that during the 1830s:

“There was hardly ever a gathering of young people that did not wind up with an ether frolic… Some would laugh, some cry, some fight, and some dance, just as when nitrous oxide is inhaled.”

Dr P.A. Wilhite, American Journal of Dental Science, 1878.

So how did these frolics lead to anaesthesia?

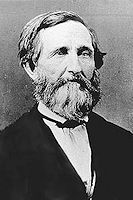

So how did these frolics lead to anaesthesia?In 1842, a 26-year-old physician named Crawford Long (portrait, right) from Jefferson in Georgia, USA, noticed the painkilling properties of ether after inhaling it at ether parties a few years earlier. He wrote that “my friends, while etherized, received falls and blows” but “did not feel the least pain from these accidents.” During one ether party, Long even stole a kiss from his future wife, which doubtless neither of them felt! Eager to try out this pain-killing drug in a medical procedure, Long managed to persuade a patient, James Venable, to use ether as an anaesthetic while Long removed a tumour from his neck. Venable probably agreed to this because he, too, had previously participated in ether frolics, and had experienced its effects first hand. According to Long, during the operation, Venable gave “no evidence of suffering” and proclaimed he “did not experience the slightest degree of pain.”

Long performed many more operations using ether, including ones to remove tumours and amputate fingers and toes. But unfortunately, he kept his discovery to himself so that he could perform further tests. Long finally published his discovery 7 years later, but by then it was too late!

|

|

|

Left: An oil painting depicting Dr John Collins Warren performing the first (public) surgery without pain as William Morton administers ether. Top right: The historic operating theatre in Massachusetts General Hospital. Top right: The ether dome in MGH.

During that 7-year delay, a US dentist called William Morton, who had heard about the use of ether anecdotally, used ether to painlessly extract a patient’s tooth in 1846. A few weeks later, Morton administered ether during an operation by Dr John Warren to remove a neck tumour from a patient at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, in front of a large audience. This was reported widely in national newspapers and medical Journals, and so Morton & Warren’s names incorrectly went down in history as the first people to use ether medically, while Long was largely overlooked. Indeed, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston still features “the Ether Dome”, and a plaque says it is the site where “the discovery that the inhaling of ether causes insensibility to pain was first proved to the world”. And in 1868 the ‘Ether monument’ was erected in the historic Boston Public Garden lauding this triumph of medical science.

The 'ether monument' in Boston Public Garden

This discovery was seen, rightly, as a huge medical advance. The Boston Daily Globe said that before the advent of ether “...surgery was torture, and a serious operation to be dreaded only less than death itself.” Indeed, until the discovery of ether (and other painkilling gases such as chloroform and nitrous oxide which were also discovery around this period), pain prevented many medical advances, and made visiting the doctor or dentist a terrifying prospect. Ether was hailed as a saviour for relieving mankind of these terrible experiences. Johann Dieffenbach, a 19th century Berlin surgeon, stated:

“Pain, the highest consciousness of our earthly existence, the most distinct sensation of the imperfection of our body, must bow before the power of the human mind, before the power of ether vapour.”

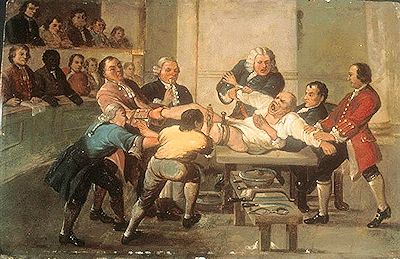

One consequence of pain-free surgery meant that surgeons no longer needed to race to finish an operation in the shortest time possible. Due to the unbearable agonised screams of the fully conscious patient, surgeons would often have bets with each other to see who could perform a surgical procedure in the shortest time! In the well-known account of an amputation in a London hospital by British surgeon Robert Liston in 1846, a man’s leg was removed - cutting though the skin, muscle and sawing through the bone, then stitching up the arteries and skin – in only 28 seconds! With the subsequent arrival of etherization which put a patient to sleep, the surgeon could now take their time and perform the operation slowly and carefully. The discovery of ether’s painkilling effects came just in time for the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and then the American Civil War (1861-1865). Ether, together with chloroform, became indispensable tools for military doctors, who used it when performing tens of thousands of amputations and other surgical procedures for soldiers on both sides. |

A drawing entitled 'Amputation' by Thomas Rowlandson, 1793, depicting the horrors and pain of surgery before ether. |

Not really, except in some developing countries due to its low price. But for many years it was the general anaesthetic of choice, replacing chloroform (MOTM October 2006) which was tricky to use due the relatively small difference in dosage required to render a patient unconscious or to kill them! However, ether is extremely flammable and often had unwanted side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, and so was replaced by other non-flammable halogenated ether molecules, such as halothane, isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane, which lessen or eliminate these side-effects. These gases are the ones mainly used today.

|

|

| Halothane (CF3-CHClBr) | Isoflurane (CF3-CHCl-O-CHF2) |

|

|

| Desflurane (CHF2-O-CHF-CF3) | Sevoflurane (CF3)2-CH-O-CH2F |

It’s often used in laboratories because it is a very good non-aqueous solvent, as described by Frobenius in 1729 in his usual effusive style:

[Taken from: An Account of a Spiritus Vini AEthereus, Together with Several Experiments Tried Therewith, Dr. Frobenius, Phil. Trans. (1683-1775), 1729-1730, Vol.36 (1729-1730), pp.283-289, available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/103540. Ubi enim ignis potentialis, ibi actuali non opus est means: For where there is a potential fire, there is no actual need, i.e. it was possible to extract these oils and essences using this powerful solvent alone, without need for heating.]

Nowadays, diethyl ether is a common solvent for the Grignard reaction as well as other reactions involving organometallic reagents.

A generic Grignard reaction. The first step uses ether as the solvent, and addition of dilute acid forms the alcohol product.

However, ether use in labs is notoriously risky because it is highly flammable.

This is due to a combination of factors. Diethyl ether boils at only 34.6°C, just under human body temperature, so it evaporates very easily. Its vapour is denser than air, so the ether fumes sink to the floor. And lastly, it is highly flammable. Indeed, ether only requires a hot surface such as a hot plate, steam pipes, lamp bulbs or a static electrical discharge from, say, an electrical switch, to easily ignite it. Even a mobile phone can be an ignition source. Many lab fires have been caused simply by leaving the top of the ether container off for a few minutes. The dense vapour travels invisibly across the floor from the unsealed vessel, and if the vapour encounters an ignition source somewhere along this trail, the flame travels back to the container - and it all catches fire. And if water is used to put out an ether fire, the burning ether will simply float on top, causing the fire to be spread over a larger area.

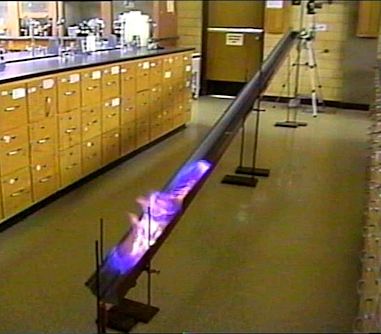

|

To prevent these fires, many labs have the rule that ether is only to be used inside a fume cupboard where an extractor fan can suck away any fumes before they can drift around and find an ignition source. An example of the flammability of ether can be seen in the ‘ether trough experiment’ (photo, left) in which some cotton balls are placed at the top end of an inclined metal trough, with a lit candle at the bottom end. A small amount of diethyl ether is then poured onto the cotton balls, some of which evaporates, and the vapour drifts down the trough to the candle. The candle ignites the ether fumes, and the entire trail of ether vapour leading back up to the cotton balls is set alight, eventually setting the cotton balls on fire. More pictures and a video of this can be seen here. Ether’s flammability also had unfortunate consequences when people drank it. |

Some people still do, mostly in Poland or Eastern Europe, but only in small amounts. But it was also popular as an alternative to alcohol in Ireland in the late 1800s (until it was later classified as a poison!).

At the time, the temperance movement was becoming popular. This was an organised attempt by religious-minded people to persuade people to abstain completely from consumption of alcoholic beverages. But because ether was not ‘alcohol’, yet drinking it produced similar intoxification effects, ether was promoted as a ‘safe’ and ‘religiously approved’ alternative to alcohol. Indeed, a priest called Father Mathew, who was a very successful temperance campaigner, called ether “a liquor on which a man might get drunk with a clear conscience”.

In Ireland, before its availability was restricted, over 17,000 gallons of ether were consumed annually, and it was said that railway carriages and markets used to reek of it.

It’s poisonous in large amounts, but the body can metabolise small amounts of ether relatively easily and rapidly, although it’s not recommended trying this! Indeed, most countries nowadays classify diethyl ether as a poison, and restrict its purchase. Drinking ether produces intoxication effects similar to those from alcohol, but they only lasts about 15 minutes, after which the drinker sobers up with no significant after-effects. However, frequent use does cause addiction and dependence.

One issue is how to drink ether at all, because the heat of the mouth is sufficient to vaporise the ether which is then exhaled before it can be swallowed. The Irish ether-drinkers solved this by first drinking a glass of cold water and then immediately drinking a small shot of ether. The water cooled the mouth sufficiently for the drinker to swallow the ether as a liquid.

Of course. As well as profuse salivation, the ether vaporising internally caused violent belching, and because at that time most illumination was by naked candle flames, the belches sometimes combusted, with explosive results! Indeed, in Russia - where ether drinking was also popular in the late 1800s – there are reports of a belching explosion killing six children and injuring 15 adults!

Nowadays it’s very uncommon, but it’s been mentioned in quite a few literary works over the years. In Tolstoy's book War and Peace which is set in 1812, Countess Rostova's sitting-room is described as having a strong smell of Hoffman's drops. This was a solution of 25% diethyl ether in 75% ethanol, whose main use was supposedly as a painkiller, but was often secretly drunk recreationally.

In Hunter S. Thompson's novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (which was made into a movie starring Johnny Depp) the author talks about the effects of ether compared to other recreational drugs: “There is nothing in the world more helpless and irresponsible and depraved than a man in the depths of an ether binge”. And in John Irving's novel The Cider House Rules, Dr. Wilbur Larch (played by Michael Caine in the movie version) is an ether addict.

|

|

|

| War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy |

The Cider House Rules by John Irving |

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson |

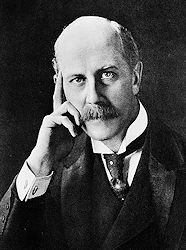

Yes, it was used before the advent of modern antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine. In 1915, during World War 1, Herbert Waterhouse (photographed in 1931, right), a London surgeon, described using ether to treat patients who had been admitted to hospital with severe septic gunshot wounds as well as other infected injuries. In one case, an old farmer had been gored by a bull and ‘ripped open from the middle of the back of his thigh to above his pelvis’. Waterhouse only saw the farmer saw five days later but by then the wound was green and infected, and the farmer was incoherent, with a high temperature and feeble pulse.

Yes, it was used before the advent of modern antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine. In 1915, during World War 1, Herbert Waterhouse (photographed in 1931, right), a London surgeon, described using ether to treat patients who had been admitted to hospital with severe septic gunshot wounds as well as other infected injuries. In one case, an old farmer had been gored by a bull and ‘ripped open from the middle of the back of his thigh to above his pelvis’. Waterhouse only saw the farmer saw five days later but by then the wound was green and infected, and the farmer was incoherent, with a high temperature and feeble pulse.

Waterhouse reported:

“Turning him on his face, I poured ether into the long, deep, grooved wound, and allowed it to boil away, filling up the groove as the ether evaporated for some minutes. Nearly a pint of ether was thus employed. I then loosely packed the wound with sterile gauze soaked in ether, and directed that the wound should be sponged with ether twice daily. Within twenty four hours the patient’s condition was all that could be desired, and the wound healed rapidly.”

Ironically, the use of ether as an anaesthetic in surgery, but not subsequently as an antiseptic, actually made surgical survival rates worse!

Because although many people now survived the immediate trauma and horror of the surgery, they later died of infection. At Massachusetts General Hospital, for example, death rates following amputations went from 19% before the use of ether to 23% afterward. The reason was that surgeons, with the aid of ether, could now operate without inflicting pain, and so they became more confident to perform surgical procedures on more complicated invasive conditions, which often involved opening the chest or gut. The number of surgeries rose rapidly, but operating theatres remained filthy due to lack of understanding of the causes of infection. Often, surgeons would operate on several patients in turn, without washing their instruments or hands in between. As a result, many patients either died, or never fully recovered, and spent the rest of their lives as cripples and invalids.

How was this solved?

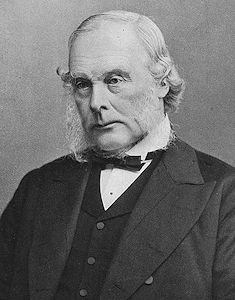

How was this solved?A young British medical student called Joseph Lister (photo, right) was in the audience for the the 28-second amputation described earlier, and although impressed by the anaesthetic properties of ether, realised that post-operative infection was still a major unsolved problem. He devoted the rest of his life to understanding the causes and nature of infection and finding a solution for it, and later went on to pioneer the field of antiseptic medicine – but that’s another story!

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.22698631]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.22698631]