Cucurbituril

by

Fabio Pichierri

Also available: HTML-only, VRML and JMol versions of this page.

Cucurbituril

(from cucurbita = pumpkin) is the fancy name given to

the pumpkin-shaped macrocycle hexamer

obtained from the condensation reaction between glycoluril

and formaldehyde (in excess):

The story of cucurbituril, hereafter

referred to as CB or CB[6], starts in 1905 (Einstein's

magic year!!!) when three German chemists, Behrend,

Meyer, and Rusche, published a paper on the

illustrious Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 339 (1905) 1.

Their paper described the reaction between glycoluril

and an excess of formaldehyde (see the above Scheme) which yielded a

cross-linked polymer (Behrend's polymer) that upon

treatment with concentrated sulfuric acid produced a crystalline precipitate. Behrend characterized the crystalline precipitate as C10H11N7O4x2H2O.

At that time, however, chemists could not make use of analytical techniques such

as x-ray crystallography that are nowadays routinely employed to identify the atomic

structure of molecules (note that in 1912, seven years later the publication of

Behrend's paper, Max von Laue

observed the first diffraction pattern from crystals).

The molecular structure of CB remained unknown for about 76 years up

until 1981 when a team of three American chemists working at the University of

Illinois, Chicago, decided to repeat the 1905 synthesis of Behrend

et al. Treatment of the precipitate (Behrend's

polymer) with H2SO4 (conc.) and subsequent dissolution in

hot water afforded a crystalline solid which, after being subjected to a

single-crystal x-ray structure analysis, revealed the beautiful pumpkin-shaped

molecule shown in Figure 1. In reference (4) of their landmark paper the

authors state: "The trivial

name cucurbituril is proposed because of a general

resemblance of CB to a gourd or pumpkin (family Cucurbitacee),

and by devolution from the similarly named (and shaped) component of the early

chemists' alembic". And another nice

chapter of the history of Chemistry was written!

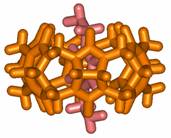

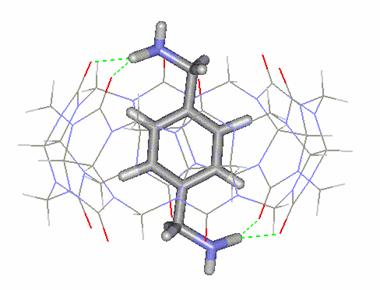

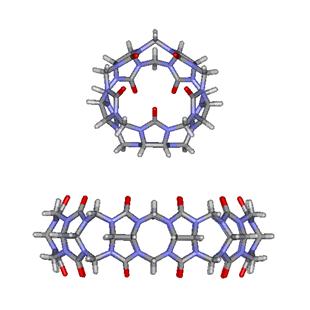

Figure

1. Molecular structure of cucurbituril:

top (left) and lateral (right) views, and Chime 3D structure (bottom centre).

The molecular dimensions of CB are as follows: the internal and external

diameters are at 3.9 Å and 5.8 Å, respectively, the height at 9.1 Å and the

volume corresponds to 164 Å3. In 1984, only three years after the

publication of the JACS paper, Freeman publishes the crystal structure of the

first host-guest complex of CB[6] which incorporates

the p-Xylylenediammonium

cation into the macrocycle's

cavity. This structure, along with those of 11 other adducts also reported in

this study, firmly established the cavitand-like

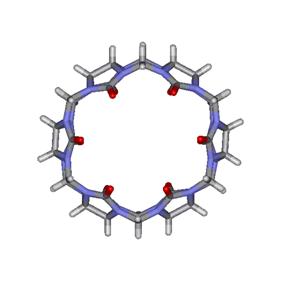

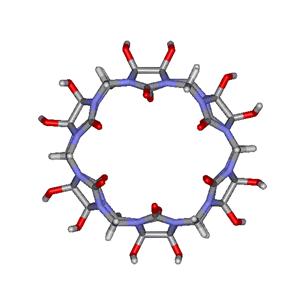

character of CB. Note from Figure 2 that each N-H moiety forms a pair of H-bond

interactions with two carbonyl (C=O) oxygen atoms on opposite portals.

Figure

2. Molecular structure of the CB[6]:p-Xylenediammonium

complex

After the exciting discoveries of the early 80s, not much happened

in the field of cucurbituril chemistry for a certain number

of years. In the year 2000, however, another important breakthrough: Kimoon Kim and his group at Pohang

University of Science and Technology (South Korea) present the syntheses and

crystal structures of three CB homologues, namely

CB[5], CB[7], and CB[8]. The crystal structure of CB[10]

has been subsequently characterized by Day's group in 2002 (as its CB[5]@CB[10]

complex – vide infra) and in 2005 by Isaacs's group (cucurbituril-free

CB[10]) whereas those of CB[9] and CB[11] are yet to be determined. Note,

however, that evidence about their existence is supported by the results of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (EIMS)

experiments.

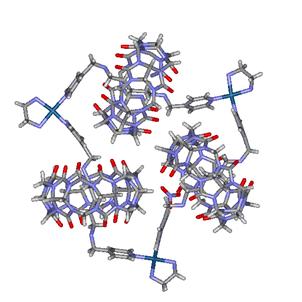

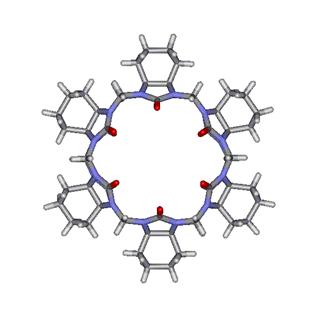

Given the unique shape of the CB[n] molecules, it is perhaps not

surprising that a large variety of interesting supramolecular

architectures have been so far discussed in the scientific literature. Figure 3

shows an example of molecular necklace that results

from the threading of three CB[6] macrocycles

onto a molecular ring containing three Pt metal centres.

Figure 3. Molecular necklace made of three CB[6] units as beads

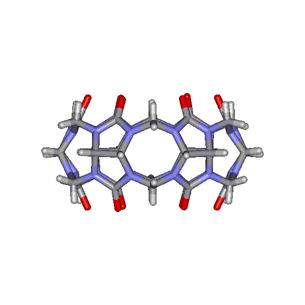

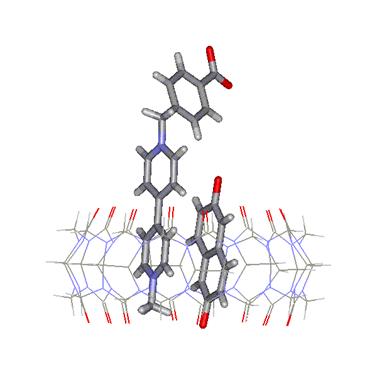

The space provided by the CB's cavity can be exploited to host

selected molecular pairs, as shown in Figure 4. The aromatic molecules brought

in close proximity can thus be activated either electrochemically or photochemically to yield products that are likely to differ

from those obtained without the presence of the macrocycle.

Hence, cucurbituril macrocycles

can be employed as molecular nanochambers or nanoreactors.

Figure

4. A molecular pair inside the cavity of CB[8]:

an example of nanoreactor

Another interesting application of CBs is in the construction of molecular

machines. According to Balzani and coworkers, "a molecular-level machine can be identified as

an assembly of a distinct number of molecular components that are designed to perform

machine-like movements (output) as a result of an appropriate external stimulation

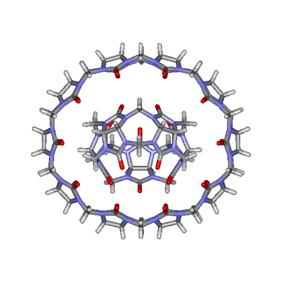

(input)." In this regard, Day and coworkers have succeeded in characterizing

the structure and solution properties of the CB[5]@CB[10] complex shown in

Figure 5. Because in solution CB[5] freely rotates inside

the cavity of CB[10], the authors classified this complex as a molecular

gyroscope (or gyroscane) in analogy with

macroscopic devices that are employed to measure and maintain orientation

during flight.

Figure

5. Molecular gyroscope made of the CB[5]@CB[10] complex

One of the main problems encountered with CB is its poor

solubility in water. In this regard, Kim and coworkers have introduced a pair

of hydroxyl groups (-OH) on each glycoluril unit as

shown in the modified CB[6] macrocycle

on the left side of Figure 6. This perhydroxylated CB[6] derivative shows good solubility in DMSO and can be further

modified with groups that can increase its solubility in water. The same group was

also able to introduce a carbon chain made of four methylene

moieties attached to each glycoluril unit, as shown on

the right side of Figure 6.

Figure

6. Modified CB[6] macrocycles

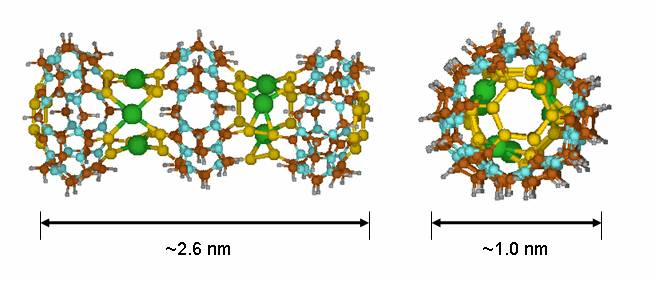

An interesting modification of CB is the replacement of its

carbonyl oxygen atoms (C=O) with sulfur atoms (C=S) which yields the thia-CB[6] analogue. Computer-aided design studies have

shown that thia-CB

macrocycles can be soldered with transition metal

ions such as Pd(II), Pt(II), or Hg(II) to produce

molecular nanotubes of any desired length and selected

diameters as the one shown in Figure 7. These new nanostructures, dubbed cucurtubes, might be useful in the development of

future molecular-scale wires for nanoelectronics.

Figure

7. Structure of a cucurtube trimer (green spheres represent Hg2+ ions)

References

R. Behrend, E. Meyer, F. Rusche,

Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 339 (1905) 1 is the original report about CB

W.A.

Freeman, W.L. Mock,

N.-Y. Shih, J. Am. Chem. Soc.

103 (1981) 7367 reports the first ever crystallographic

characterization of the molecular structure of cucurbituril,

CB[6]

W.A. Freeman, Acta Cryst. B 40 (1984) 382 describes the

host-guest complexes of CB[6]

J. Lagona, P. Muchophadyay,

S. Chakrabarti, L. Isaacs, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44 (2005) 4844 is the most

comprehensive review written on the cucurbit[n]uril

family of macrocycles – a must for the CB fans!

J. Kim et al, J. Am. Chem.

Soc. 122 (2000) 540 describes then syntheses and crystal

structures of CB[n], with n=5,7,8

A.I. Day et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 (2002) 275 describes the molecular-scale gyroscope made of the CB[5]@CB[10]

complex

F. Pichierri, Chem. Phys. Lett. 390 (2004) 214

reports the results of the first DFT calculations on CB[6]

and its sulfur analogue, thia-CB[6]

F. Pichierri, Chem. Phys. Lett. 403 (2005) 252 presents the computer-aided design of

tubular nanostructures obtained from the nanoscale

soldering of thia-CB[6] units with transition metals

V.

Balzani et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39 (2000) 3348 an excellent

review on molecular-scale machines

The crystal structures depicted on this page were retrieved from

the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) maintained by the Cambridge Crystallographic

Data Centre (CCDC), 12 Union Road, Cambridge, CB2 1EZ, UK

◊◊◊◊◊

I dedicate

this MOTM page to my lovely family.