![]()

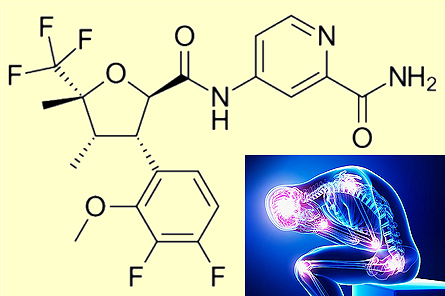

Suzetrigine

A new non-addictive painkiller

![]()

![]()

Molecule of the Month May 2025

Also available: HTML version.

![]()

Suzetrigine

SuzetrigineA new non-addictive painkiller

Molecule of the Month May 2025

|

Suzetrigine |

But don’t we have non-addictive painkillers already, such as aspirin and paracetamol?Yes, but these are usually used for low levels of pain, and they have side-effects which prevent high dosages or long-term use. Long-term use of aspirin (MOTM for February 1996) can cause increased bleeding, indigestion and stomach ulcers. Paracetamol (MOTM September 2020) can cause serious liver damage if taken at too high dosages. Ibuprofen (MOTM for November 2001) at high dosages can cause ulcers, bleeding, or holes in the oesophagus, stomach, or intestine. So, although these drugs are perfectly safe at low dosages, they cannot be easily used to treat very severe or chronic long-term pain. |  Many simple painkillers, such as aspirin, paracetamol and ibuprofen are available from any pharmacy. |

|

|

|

| Aspirin | Paracetamol | Ibuprofen |

For localised pain, local anaesthetics such as amylocaine, novocaine (often used by dentists for tooth extraction), and lidocaine are used. These drugs are usually amino amides or amino esters. They have the suffix "-caine" because cocaine (MOTM February 2016) was originally used as a local anaesthetic. Although most of these drugs (except cocaine itself) are not addictive, they only work locally, and so are usually given by injection close to the site of pain, for example during surgery. But repeated injections over long periods of months or years is not really practical to solve chronic pain.

|

|

|

| Procaine (Novocaine) | Novocaine is a local anaesthetic used by dentists. |

This is where the opioid drugs come in. The name comes from the opium poppy from which most are derived, and the first one of these to be discovered was morphine (MOTM for Nov 2004). But then chemists synthesised many more, such as codeine and oxycodone (MOTM Dec 2015), heroin (MOTM March 2023), methadone (MOTM April 2023) and fentanyl (MOTM March 2015). These drugs are very effective at treating even severe pain, and so have been the prescription painkiller of choice for many years, particularly in the US. However, they are also so addictive that people continue to use opioids even after the original cause of pain has subsided or gone away. This can lead to dependency - using the drug continuously to prevent withdrawal symptoms, rather than to treat pain.

The number of deaths in the US involving any opioid from 1999-2022.

[Image: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

It is believed that the over-prescription of opioids in the 1990s directly or indirectly caused the deaths of 645,000 Americans between 1999 and 2021, and this healthcare catastrophe was dubbed "The Opioid Crisis". Things became even worse when fentanyl became popular as an illicit recreational drug in the early 2020s. At least one type of opioid was implicated in 72% of overdoses in the US in 2023, killing three times as many people as cocaine.

I'm not surprised. After a few high-profile court cases, many books have been written about the opioid crisis, and some of these have been turned into movies or TV miniseries.

|

|

|

| The Netflix series Painkiller which focuses on the birth of the opioid crisis, and Purdue Pharma, the company that manufactured OxyContin. | The TV miniseries Dopesick was based on the book Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy. It focused on how the opioid epidemic started and the people in the US affected by it. | The Crime of the Century is a 2-part documentary which follows the US opioid epidemic and the politicians, government regulations and corporations that enabled opioid abuse. |

When a pain stimulus is received, for example when cells are damaged, nerve cells are activated which send a signal to the brain, which is interpreted as pain. The signal is transmitted by sodium ions moving through the nerve cell membrane, changing the local voltage causing current to flow down the nerve. The passageways through the cell membrane through which the Na+ ions move are called sodium channels (or receptors). If these channels are chemically blocked or deactivated, the signal is stopped, and the pain signal never reaches the brain.

But there are 9 subtypes of sodium channels located around the body, labelled NaV1.1 to NaV1.9, where the ‘V’ refers to the channel being controlled by a change in voltage. Some are found in nerve cells within the brain itself, whereas others are in peripheral nerves in, say, the arms and legs.

Opioid drugs target receptors in the brain which kills pain, but this has a side-effect of releasing dopamine (MOTM October 2008), the body’s ‘pleasure hormone’, which produces emotional ‘highs’ which lead to dependency and addiction. Local painkillers, such as procaine (novocaine), block all of the sodium channels indiscriminately, which is why they must be administered close to the site of the pain — through injections or skin creams and gels — to avoid widespread side effects. However, for a painkilling drug to be more universally useful, it needs to be given orally via a pill, rather than an injection. But such a drug administered to the whole body must only target the required sodium-channel sub-type, not all of them all over the body, or the results might be deadly.

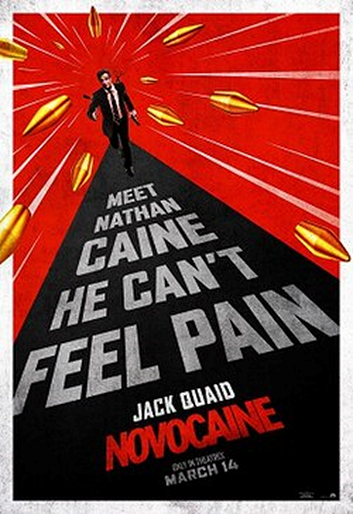

The 2025 movie Novocaine starring Jack Quaid is about a man who cannot feel pain, presumably because his NaV1.7 receptor is blocked! |

So ideally, a drug needs to target only the sodium channels in the peripheral nerves, not those in the brain?That’s correct. In fact, 3 of the 9 sodium channel subtypes, named NaV1.7, NaV1.8 and NaV1.9, were recently discovered to be located only in the peripheral nerves, so if only these channels were to be blocked there might be far fewer dangerous side-effects. And that’s where Suzetrigine comes in?Precisely. Suzetrigine targets the NaV1.8 receptor in the peripheral nerves. Because it is not located in the brain, blocking this receptor doesn’t trigger pleasure responses or illicit dependency. How was this discovered?In the mid-2000s, genetic studies revealed that one of those 3 peripheral receptors, NaV1.7, was implicated in two pain-related oddities. In the first case, a Pakistani street performer was found to have a complete inability to sense pain. To entertain crowds he walked on hot coals and stabbed himself! Like in the movie, Novocaine?Yes, but without a happy ending. Being immune to pain, the performer became rather blasé about the risks of potentially dangerous activities, and died after jumping off a house roof. Examination of his body showed that he had a genetic defect which knocked out his NaV1.7 receptors. Some of his family members, who also lacked the ability to feeling pain, were also found to have the exact same genetic defect. |

In the second case, two Chinese families were reported to share a genetic defect causing their NaV1.7 channels to be overly stimulated – leading to an affliction called 'primary erythermalgia'. This rare disease causes intermittent burning pain with redness and heat in the extremities, and is sometimes referred to as ‘Man on fire’ syndrome. The conclusions were that blocking NaV1.7 stopped pain, while overstimulating it made the pain intense and continuous. So NaV1.7 became the target?Yes. A lot of effort and money was spent by numerous drug companies trying to find potential drugs to inhibit only NaV1.7 and no others, but nothing really worked well enough. But the idea of targetting the 3 peripheral receptors was still sound. So, attention then switched to the next one, NaV1.9, but this proved challenging to study and to target in the laboratory. So NaV1.8 was the final choice, and this line of research proved more fruitful. After a lot of work, the pharmaceutical company Vertex Pharmaceuticals from Boston, MA, USA, found a drug that blocked NaV1.8 over 30,000 times more strongly than the other sodium channels – in other words it killed pain and was highly selective. Originally called VX-548, it was renamed Suzetrigine, and is now being marketed under the brand name Journavx. |

Erythromelalgia in hands of a 52-year-old Scandinavian man. [Image: Minor, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons] |

So this is quite a big breakthrough?

So this is quite a big breakthrough?Yes, in January 2025, suzetrigine became the first new class of painkiller for decades to be approved for medical use in the United States by the US FDA. It suppresses pain at the same level as an opioid, but without the risks of addiction, sedation, or overdose, and can be used to treat moderate-to-severe acute pain in adults. There are currently trials for its use in chronic back-pain and pain in the fingers and toes resulting from diabetes.

Of course, but these are minor compared to those from opioids. Mild side-effects may include itching, muscle spasms, rashes, nausea, constipation, headache, and dizziness. But long-term safety and side effects remain unknown.

Not necessarily. Whether the drug becomes a viable alternative for opioid drugs depends upon its price – suzetrigine is currently far more expensive than most cheap opioid painkillers. But the lack of addictiveness is its trump card, which may make it one of the most important drug discoveries of the last decade. And now that scientists know that targeting NaV1.8 works, a host of other painkillers that work in the same way are under development.

![]()

![]()

![]() Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.28706393]

Back to Molecule of the Month page. [DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.28706393]